Articles

| Name | Author |

|---|

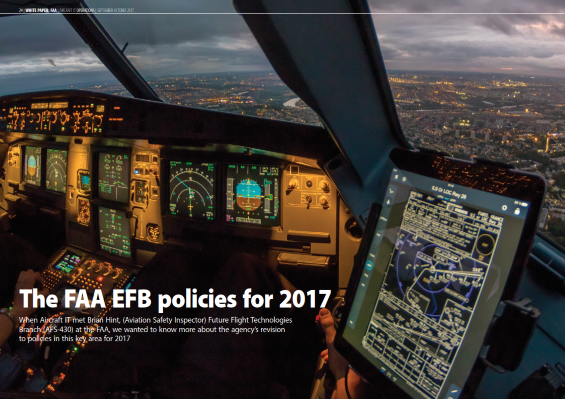

The FAA EFB policies for 2017

Author: Brian Hint, Aviation Safety Inspector (Operations), Federal Aviation Administration (FAA)

SubscribeThe FAA EFB policies for 2017

When Aircraft IT met Brian Hint, (Aviation Safety Inspector) Future Flight Technologies Branch (AFS-430) at the FAA, we wanted to know more about the agency’s revision to policies in this key area for 2017

This article looks at the FAA’s policies with regard to electronic flight bags (EFBs) including changes being introduced at the headquarters level and the effects that has on how the principal inspectors (PIs) make their decisions with regard to operators’ EFB programs. Who better to go to then than Brian Hint who, in his position in the Future Flight Technologies Branch (AFS-430) at the FAA, is as well placed as anybody to know what the future holds for FAA policy regarding EFBs. Of course, sometimes, when it gets complicated such as when dealing with installed components, there may be others involved, like the principal avionics inspector or the maintenance inspector. But the intent behind the policy, including advisory circulars (ACs) for operator utilization and Inspector guidance for the FAA’s inspector force, is being developed through the Future Flight Technologies Branch.

The FAA tries to keep things general but when questions about specifics or things that aren’t addressed in the policy come up, that typically goes to the headquarters level. As Brian explained; ”We try to get everybody reading from the same page by developing standards and incorporating lessons learned into the new policy. That’s the ‘evolving’ way this policy has been working. In the past six years, this will be the fourth amendment to the FAA’s EFB policy.”

There were four principal topics that we wanted to cover: the main document AC 120-76D, the guidance that industry and manufacturers utilize; also, we wanted to look at the 8900.1 changes; and specific flight inspector handbook changes because, as Brian put it, “It’s important for readers to realize the interaction between both of these documents.” Another important subject that we wanted to include was changes to the EFB program management and we wanted to discuss attitudes on the inflight display of own-ship position for various EFB applications.

STATUS UPDATE ON AC 120-76D

Our first question though, was a little more procedural: the place of comment adjudication in this FAA process. “The FAA issued this advisory circular at the end of 2015;” Brian explained. “It was out for 60 days and came back at the beginning of February 2016. We incorporated comments and people in the industry quickly heard about the changes that we were and weren’t going to make and became quite vocal – see below. But, of the 250 odd pages of comments that the FAA received, it was possible to incorporate the vast majority of those comments and the intent behind those comments.”

He continued, “A lot of the comments had to do with EFB program management such as ‘we’re not going from paper to digital anymore; we’re managing an EFB program so the material that used to matter no longer applies.’ But there were inspectors from different parts of the FAA taking different approaches and, as a branch that works to establish standards, we wanted to see standardization. So we took back the AC and changed the policy.”

This ties directly to ‘own-ship position in flight’ which is, Brian confirmed, “… a much bigger matter than just the display of own-ship position, especially for avionics manufacturers as well as software and hardware manufacturers of commercial off-the-shelf equipment.” (See below).

Having considered how comment incorporation impacts the process, we also needed to follow through with understanding the process to publishing. Given that the majority of comments were incorporated after they were adjudicated, where are we today? “After the Tech Writers had worked on the document, it went back out, because of the amount of change, for a concurrent Public and Internal Review.” Was Brian’s first response; then, “The FAA broadcast publicly that it was looking for an end of May 2017 final publishing date. This was not achieved due to a formal request by industry to extend the public comment period by 30 days. In addition, because of substantial changes to internal guidance (i.e., 8900.1 changes) and the fact that all policy documents need to be published concurrently, we are looking at August or September 2017 for a final publication date.”

ORDER 8900.1 CHANGES

Having mentioned 8900.1, we asked Brian to expand on the changes in this, the thinking behind them and what their impact will be. His answer was thorough. “There used to be an AC that the industry read and then there would be a copy and paste (for the most part) of that document in an 8900.1, the Field Inspector’s Handbook. But there is now a cultural change going on inside the FAA. It used to be that the FAA inspector only read the Field Inspector’s Handbook, they didn’t care about the AC, because ACs are for the industry; the Handbook covers what they have to do. Realistically speaking, that’s tough: from an administrative perspective, as a policy writer, it would mean there has to be a duplicated effort, one way for the industry and another way for FAA field inspectors which makes no sense. So FAA leadership determined that enough was enough and that if the 8900.1 is to be written one of the first things it should say to the inspector is ‘Read the AC’ so that everybody is reading from the same page. Don’t duplicate anything in the 8900.1; make it written in one place which makes sense administratively. Then, finally, if there are any questions, there are people at headquarters who can be contacted.”

It all makes sense on paper and in theory, but we wondered about the time element and associated issues. Brian confirmed, “It’s going to take time so, during that transition, there might still be some lack of standardization; however, this is an effort to get rid of that. The good news is that the new version (Order 8900.1 Vol 4, Chapter 15) is drafted and ready for review. With the Order 8900.1, Vol 3, Chapter 18, the table that readers see has descriptions of the hardware and the software that the operator was authorized to use. There wasn’t a lot of specific backing as to how an operator/CMO (Certificate Management Office) should fill out that information; there was a lot of non-standardization and a lot of changes. So, thinking about all the operating software changes, all the application updates, some were entering specific software versions into the OpSpec table, some weren’t; anyway we learned that there’s a great deal of change within EFB and the program management side of the house for the operator.”

“So we finally said ‘enough is enough’; now A061 which is the authorization for an electronic flight bag program which is still authorized by the principal inspector, simply says that ‘these are the make/model/series aircraft that have an authorized electronic flight bag program’ and now the operator just says ‘I have authorization; the specifics behind that are somewhere else’. That idea was reviewed by an industry regulator forum called the OSWG (OpSpec Working Group) and the feedback was well accepted.”

EFB PROGRAM MANAGEMENT

Since their first appearance, EFBs have developed rapidly but how, we asked, has this development impacted on the FAA’s planned changes. In response, Brian pointed to a particular aspect of that development. “A key consideration here is that we’ve moved on and are not necessarily going from paper to electronic means any more. The industry fought hard and said ‘there have been a lot of changes, we need to be able to do stuff on our own’ and that makes sense: plus, guess what? From the FAA’s perspective for our PIs, they already have a plethora or responsibilities and duties, so that was also good for us. We realized that there are operators who are already doing this on their own; there are principal inspectors that allow a certain degree of leeway for those operators because they do the right thing. And so the FAA said, ‘OK fine’ and from an administrative point of view, the information that used to be in the OpSpec, that’s specific hardware, software, what iOS version, what applications, what their version are… all those things had to be tracked administratively; we call that a Program Catalog. That Program Catalog is now maintained by the operator; and, if a PI needs to see or have access to that program catalog, they just specifically ask for it.”

So, if more of the responsibility will in future rest with the operator, what will they be able to manage? Brian acknowledged the question. “This is important,” he emphasized. “These are the things we’re saying that the operator, within given parameters is allowed to manage in respect of their own EFB program.” We’ve separated the three parts of his answer.

- Type A: those matters that have no effect in terms of hazard severity can be updated or added to by the operator without the need for further authorization.

- Type B: if the operator already has authorization for their type B application and it needs to be updated or there need to be changes to training or there’s a flight crew bulletin going out about it, the FAA will have to approve the change to training. Therefore, if an operator needs to update a type B EFB application, they can do that themselves, they don’t necessarily have to get their PI involved.

- Incorporating OS updates: This, according to the industry is the 90% solution to handle a lot of changes that are occurring today. For everything else, that’s when operators need to have PI involvement, e.g. adding a type B application, new hardware or a new aircraft type arriving in the fleet. The degree to which the FAA gets involved is dependent upon the relationship that the operator has with their PI and both looking at it from the perspective of what makes sense to validate that this new hardware/software/procedures/maintenance all works.

In essence, as Brian told us, during the above process, the FAA looked at some companies who it was felt had been doing it right and considered what their process was and put that down on paper to establish some industry best practice parameters.

INFLIGHT DISPLAY OF OWN-SHIP POSITION

There was an outcry from the industry in 2016 concerning this matter; so the FAA met with them. In that spirit, we wanted to know about four things regarding own-ship. When can it be used; what’s the position source; is there going to have to be already existing glass such as a Navigation display that has similar information; and where can this go in the cockpit? These are all things that aircraft certification, flight standards, and industry wanted to talk about. The FAA received that feedback and then talked internally to “thrash it out” as Brian put it. He then explained to us the end results which the FAA thinks that operators will be pleased with and which we’ve set out below.

Own-ship position in-flight

In terms of phase of flight, Brian told us, it should be seamless; on the ground, in the air, back on the ground, there shouldn’t be any difference about when a display of own-ship position can be available on various applications such as weather, aeronautical information… those types of applications which the FAA specifically identifies in the back of the AC to make it easier for users to interpret the newest language. The FAA specifies the things on which own-ship can be displayed because those are the things on which it could possibly be displayed such as oceanic navigation and plotting, the things that are already in the AC, that the FAA thinks might encourage operators to put display of own-ship position on.

Going further into the topic, Brian added, “Right now, AC120-76C talks about a 40 meter total error budget between the navigational database and the errors described in documents like DO-272 (User Requirements for Aerodrome Mapping Information) and the GPS source. Typically, if there is an installed GPS source, performance values are indicated and the FAA will also allow that for commercial off-the-shelf GPS sources. However, in the air, the FAA doesn’t really care about an error budget it just needs the device/source to perform its intended function. So, we had a job aid and it described in detail how to collect and track information over a period of time at a representative sample of airports. It was objective data that would be provided to the PI to ensure that that GPS source was providing accurate information. So, what’s the difference between tracked data or something subjective that says ‘OK, I’m on November holding short of Papa’. Look outside and that’s where the aircraft is; look inside and that’s where it’s shown to be. We made it a little more Rocket Science than was really necessary but this is from a historical perspective so people will need to bear with us; the plan is to eliminate that job aid, realizing that you need to provide your PI with feedback so that they know that, on the ground, if own-ship is on, it will be within this (now 50 meter) total error budget.

“In the air, however, we knew that, first off, the subjective data was going to really tough for providers such as those that might be reading this to be able to give to the PI. So we thought about it at the FAA and said, ‘wait a minute, nobody’s navigating off this information’. Display of own-ship on aeronautical charts is really just a quick way of orienting to a north-up map; it doesn’t have to be specifically a north-up map but the utilization of aeronautical charts typically for a pilot is north-up whereas the information in front of them is for forward path movement (i.e. heading-up.)”

So, the FAA is saying, ‘we ‘recommend’ a GNSS source because we know the technology’s out there but that isn’t a ‘must’: if you have another source that’s able to provide an accuracy or performance value that must show where you are in relation to the other instruments.’ To illustrate the case, Brian explained, “If you’re 50 miles from the Sea Isle VORTAC, see that on the Nav display or DME (distance measuring equipment) and look down and it shows about 50 miles from Sea Isle on the aeronautical chart, that makes sense, it seems to work. So that’s the type of information that the FAA thinks is legitimate to provide to the PI.”

Against all of the above, there is also a downside. There are people within the FAA and the industry who think that there’s a risk involved with providing misleading information on a commercial off-the-shelf device. What, we wondered, is the FAA proposing to satisfy and ensure that everyone thinks that this is a safe thing to do? Brian’s reply was that, “The requirement is for two things: big picture, Reader’s Digest version; yes, have glass. This is not just own-ship here, this is anything; this is a major change in the way that we describe functions in the EFB because, remember, in a few years from now, it’s not going to be EFB anymore, it’s commercial off-the-shelf software providing pilots’ information potentially anywhere in the cockpit; not just portable, it could be an installed display. These are the key terms that we’re going to be looking for when anything new is going to be displayed in the cockpit.

“First, Concurrent Use. This means the aircraft must have a system installed under certified type design displaying operationally similar information for each EFB own-ship application in that cockpit. In the unlikely case that there was misleading information on, say, a portable commercial off-the-shelf display using a portable GPS device or maybe even internal to that unit; if it’s displaying misleading information: obviously, the flight crew have been trained to use a primary flight display to fly the aircraft; they use the Nav display for situational awareness and third they use this EFB. We’re just relying on the glass because we know and understand the difference between having the situational awareness for the pilot when there’s glass in the cockpit on a Nav display or just having the round dials. So the FAA will not mess with the risk and is saying that users need concurrent use. Does that mean that, if you’ve got a 737-300 and you’ve got analog instruments that you can’t do own-ship position in flight? No, it doesn’t. But what this AC (advisory circular) addresses is not that case. This AC says, ‘if you have this, you get this’. If it’s something outside that realm, that’s the type of discussion that you’ll need to have with your principal inspector, the CMO (Certificate Management Office), with the PAI (Principal Avionics Inspector) to figure out what are the concerns, what are the risks involved and then mitigate against those risks. So this is a green light or, rather, a yellow light if you don’t have glass in the cockpit.

“Second, Differentiation. The flight crew must be able to distinguish between the installed primary avionics display and the supplemental or ‘secondary’ EFB display. This concept is straightforward for portable EFBs but, for shared displays, further evaluation of the installed avionics display is required under type design. The certified sources are primary, secondary sources are not. This isn’t just limited to own ship; this is anything that can be described to have, with concurrent use and differentiation, a hazard effect of minor or no effect.”

Having received very clear answers throughout, we finally asked Brian about where any unit displaying own ship should be located. As before, he explained the FAA position. “The FAA doesn’t care whether the unit is portable or installed, we’re agnostic. But if you are going to put own ship on an installed provision there will have to be aircraft certification involvement. First off, because you’re displaying that information on an installed product, AC 20-173 is immediately going to come into effect because there has to be an aircraft interface device for partition and protection pushing that information from the EFB to the installed display. But also, because of this idea of own-ship and, now, concurrent use and differentiation, Aircraft Certification realizes that there’s going to be a plethora of additional information that may be driven from EFB onto installed glass which, from a pilot’s perspective may be a really good thing. I may not want to have information off to my side, I may want it directly in front of me; but there might be appropriate and not appropriate ways of displaying that information. That’s more of a Human Factors issue and that’s why Human Factors specialists within aircraft certification ought to be looking at that specifically, especially when we put stuff like own-ship position on installed displays. So, AC 20-173 is going to be revised this year.”

Our time was up but before leaving we thanked Brian for some excellent and comprehensive answers which we know will be valuable for readers keeping up in this fast changing aspect of aircraft Operations technology.

Contributor’s Details

Brian Hint

Brian Hint is an Aviation Safety Inspector (Operations) with the Federal Aviation Administration. For the last seven years, he has supported the Future Flight Technologies Branch (AFS-430) located at FAA Headquarters, Washington DC. The focus of the branch is the integration of evolutionary and revolutionary technology, along with new technology-based operations, into the FAA’s vision for the Next Generation Air Transportation System. Brian is the FAA Flight Standards subject matter expert for Electronic Flight Bag and Aeronautical Information Standards Development. Brian has over 18 years of aviation experience with both the military and civilian part 121 air carriers.

Brian Hint is an Aviation Safety Inspector (Operations) with the Federal Aviation Administration. For the last seven years, he has supported the Future Flight Technologies Branch (AFS-430) located at FAA Headquarters, Washington DC. The focus of the branch is the integration of evolutionary and revolutionary technology, along with new technology-based operations, into the FAA’s vision for the Next Generation Air Transportation System. Brian is the FAA Flight Standards subject matter expert for Electronic Flight Bag and Aeronautical Information Standards Development. Brian has over 18 years of aviation experience with both the military and civilian part 121 air carriers.FAA

The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) is the national aviation authority of the United States. An agency of the United States Department of Transportation, it has authority to regulate and oversee all aspects of American civil aviation.

The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) is the national aviation authority of the United States. An agency of the United States Department of Transportation, it has authority to regulate and oversee all aspects of American civil aviation.Comments (0)

There are currently no comments about this article.

To post a comment, please login or subscribe.