Articles

| Name | Author | |

|---|---|---|

| Case Study: PIC – Pilot in Command or Processor in Command? | Ping na Thalang, Vice President Information Systems Dept, Bangkok Airways | View article |

| White Paper: Business Intelligence – More than information alone | Gesine Varfis, Managing Consultant, Lufthansa Consulting | View article |

| White Paper: Fuel Efficiency through IT Support | Captain Marcel Martineau, President and CEO, TFM Aviation Inc. | View article |

| White Paper: Designing the Enterprise Solution | Lawrence A. ‘Bud’ Sittig and James R. Becker, Flight Guidance LLC | View article |

| Case Study: EFB – Posing Questions and Offering Answers | John Christian Paulshus, Head of Business Development Operational IT Solutions, Norwegian | View article |

White Paper: Fuel Efficiency through IT Support

Author: Captain Marcel Martineau, President and CEO, TFM Aviation Inc.

SubscribeFuel Efficiency through IT Support

Balancing safety, service quality, efficiency and relative costs within the operational envelope, explains Captain Marcel Martineau: President and CEO TFM Aviation Inc. is everybody’s concern

As Airlines continue efforts to improve fuel efficiency, both in terms of consumption and impact on the environment, plus to take heed of the European Union’s recent publication of limits for Airlines’ CO2 emissions, the need to maintain the focus on efficiency is more important than ever. This article details some IT tools that will assist in reducing fuel consumption and CO2 emissions while supporting enhanced safety and operational efficiency.

The recent and sudden rise in fuel costs has renewed concentration on operational efficiency because fuel represents the major portion of an airline’s total budget. Recent international events, political upheavals or environmental disasters, reinforce the point that the price of oil is beyond the control of the airline industry and that each airline must have a proactive fuel management program in place to mitigate the effects of price volatility. While the cost and environmental impact of fuel consumption are high, they must be weighed against other considerations such as on-time performance, misconnections, customer service, etc.

Fuel Management and Safety

Managing fuel accurately will not only reduce waste and improve the environmental impact of an airline’s operation but it will also improve safety. An airline will need to acquire tools to track fuel consumption throughout the operation and ensure that every stakeholder shares a clear understanding of how fuel is to be managed. The availability of accurate data and proper statistics will increase overall awareness of fuel management while reducing the risk of unplanned diversions or landings caused through inadequate fuel reserves.

Saving fuel can make the difference between profit or loss

Historically, airline operating margins have been small. To realize one dollar in profits, airlines that are fortunate enough to have a 4% return on investment must generate at least $25 worth of sales while spending only $24 dollars to provide the service. Even one dollar saved in fuel costs will go straight to the bottom line. The most successful airlines today have an adequate fuel and operational management program that involves not only the Flight Operations Department but all company departments and personnel who can impact fuel consumption. Ground Services, Maintenance and Engineering are just a few of the departments that should be involved in this decision making process.

Many Airlines feel comfortable with their present level of fuel efficiency. The problem is that airlines are sometimes unaware of where and how much fuel is wasted. Also, interdepartmental rivalries and poor communication often prevent the cooperation that is required to operate efficiently throughout the Company. One such example is where Ground Services may cut back on ground support equipment maintenance resulting in an excessive use of on-aircraft auxiliary power units (APU). It is only by requesting independent advice from professionals that an airline can really be certain that it has a balanced approach to fuel and operational management.

Organization and Communications

The Integrated Operation Control Centre (IOCC) is responsible for the daily operation of the airline. This department must be able to track every flight and be able to take the most appropriate decisions while maintaining good customer service and protecting the company’s interests. Proper IT systems are essential for the efficient and safe operation of the airline.

The IOCC must be able to communicate instantly using a real time on-screen messaging and alerting system connecting with every flight as well as all departments including Flight Dispatch, Crew Scheduling, Maintenance, Aircraft Route Control, and Weight and Balance. All communications must be automatically routed and redirected to appropriate users and archived as required. Instant communications are essential especially during irregular airline operations where time is of the essence. Dispatchers must be able to immediately uplink and downlink messages to and from aircraft.

Having immediate access to flight information, operating times, briefing packages, MELs, the flight’s fuel state, and instant messaging will improve reaction times while minimizing costs by supporting the best decision(s) under critical conditions. Irregular operations cost airlines dear, in addition to creating hardship for passengers. The situation can very rapidly become confusing, therefore being able to assess the situation quickly will improve decision making and minimise the operating costs and flight disruptions.

Having adequate flight tracking will not only allow the airline to manage its operation efficiently but also it will reduce recovery time and cost. Missed connections in addition to reducing customer service will result in seat spoilage, lost revenues and reduced overall efficiency in terms of fuel per seat kilometre.

Fuel Policy

An airline’s fuel policy is an extremely important document that not only regulates fuel usage but also ensures safe operation: airlines must always ensure that their fuel policy is up to date. The EU OPS fuel regulations provide excellent guidance allowing airlines to benefit from appropriate IT fuel management tools permitting the use of statistical contingency fuel, no-alternate flights, lower landing limits based on the aircraft and airport landing capabilities, and en route decision point planning where the contingency fuel can be reduced.

Airlines need fuel management tools such as an advanced fuel management information system to ensure that, once an adequate fuel policy is in place, all participants adhere to the best practices established in that fuel policy. An adequate fuel management tool is not simply an accumulation of data, but it must have the business intelligence capabilities to facilitate use of the strategic information on a day-to-day basis by the airline’s managers and operating personnel. Statistics on flight burn variations from plan for instance must be readily available to allow pilots and dispatchers to assess the risk associated with a particular city pair and take the most appropriate decision when boarding extra fuel. This will not only reduce wasteful practices but will also minimize the chances of unplanned diversions.

Flight Planning

Flight planning systems are at the heart of an airline’s operation. Many airlines have upgraded their flight planning systems and the return on investment (ROI) is relatively short especially when the enhanced systems’ capabilities are introduced promptly. Also, dispatchers must be properly trained to utilize the capabilities of the improved flight planning system and there is a requirement to increase the proactive role of flight dispatchers. In today’s ever more complex and dynamic operating environment, pilots often do not have access to all of the appropriate information or the time to properly optimize the extra fuel to be carried and perform adequate risk management.

Some airlines take advantage of their advanced flight planning system capabilities to pre-compute flights several hours before departure, performing an initial assessment of the impact of winds and other weather factors on their operation. Flight planning systems that can pre-calculate flight profiles will reduce the dispatchers’ workload during final evaluation of flight plan profile options. In the case of North Atlantic flights for example, pre-calculating routes via the North Atlantic tracks, then avoiding the tracks along with other random route options, assessing various speeds, vertical profiles and load options, will improve optimization and reduce operating costs. Once the initial flight options are integrated to the Gantt chart, the IOCC Manager will be able to perform a pre-assessment of the operation and coordinate with dispatchers to select the best options, after assessing the potential for delays on the rest of the operation.

Taking advantage of Cost Index optimization will reduce operating costs and improve on-time performance: Cost Index is a factor that balances the cost of time with the cost of fuel. Once the cost of time (i.e. crew costs, maintenance costs and delay costs) has been calculated, the cost of time in dollars per minute (e.g. US$ 30/min.) is divided by the cost of fuel in dollars per kilogram (0.75 US$ per kg); this will yield a Cost Index, in this case, of 40. In other words, as long as the flight burns less that 40 kg of fuel to save one minute, the airline is ahead in terms of total cost. Since the price of fuel can change from airport to airport or the cost of fuel can vary significantly over short periods of time, it is important to adjust the flight Cost Indices frequently in an effort to minimize operating costs.

One important factor when calculating Cost Index value is to measure the cost of arrival delays and, in this, it is important to understand that the cost of delay is not linear. The initial delay minutes might not be overly expensive but as soon as connections start to be affected, delay costs can escalate rapidly. That rapid escalation in the cost per minute will justify the use of much higher Cost Indices for delayed flights. However, this must not be done in isolation and the impact of the delay must be viewed in terms of the overall airline operation. It might be possible in some cases to hold the connecting flights and then accelerate them or to accommodate passengers on subsequent flights, assuming of course that seats are available. Other considerations when calculating delay costs are passenger goodwill, hotel and meal costs, gate costs, staff costs, and the impact on subsequent flights. The system must be forward looking and include multi-segment costs for delays.

As airlines increase their ability to fly long distances, it is essential that they optimize flight routings, speeds and altitude profiles, payloads and over-flight costs. Planned flight times should be adjusted when necessary to minimize delay costs. The airline’s flight planning system must be capable of calculating variable speed flights using proper Cost Index speed optimization and vertical profiles to minimize overall flight costs. With proper delay costing tools, it is possible to determine a target arrival time that will result in the minimum overall cost for the airline by trading the fuel cost of acceleration against the costs of delay. Note that accelerating flights should be a last resort and all possible measures should be taken to minimize delays on the ground. Flights can also be slowed to save fuel by using reduced Cost Index based speeds to avoid early arrival costs such as gate conflicts or ground service personnel issues.

To properly optimize flights an accurate flight planning system is required and many factors can impact on the accuracy of a system. Advanced planning systems will select departure and arrival runways in addition to the proper departure and arrival procedures. Additionally, the system must be able to accurately calculate the flight times and profiles for optimized Cost Indices values.

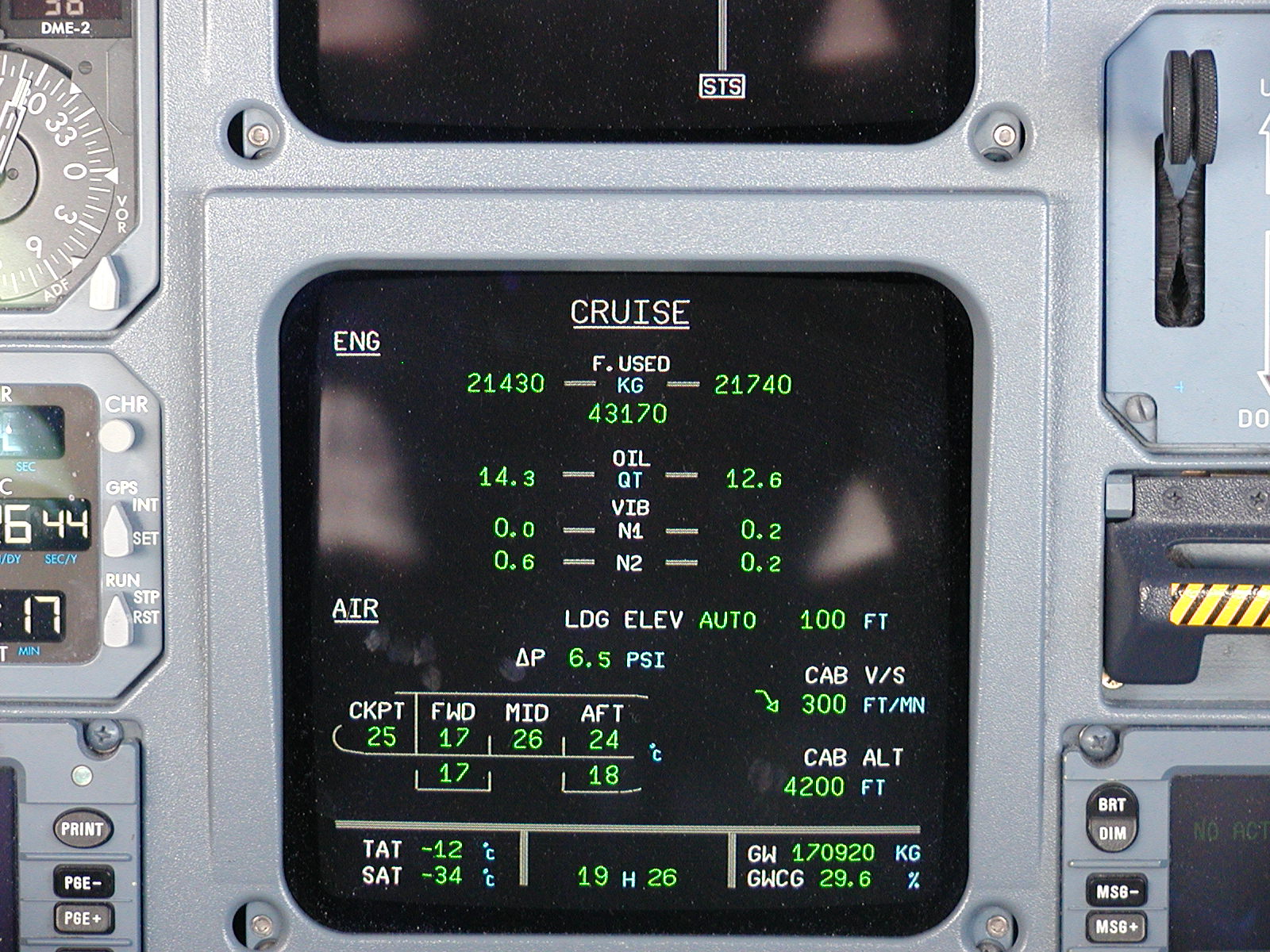

A system must also include accurate fuel burn biases: while a new aircraft might perform close to the flight plan calculations (even new aircraft fuel burns can vary from the system calculations) it is not unusual to find a variation of as much as 5% between new and older aircraft. Some aircraft types may initially lose up to 1% in burn per year, depending on the flight hours and cycles. One can easily imagine the impact of inaccurate fuel burn biases on long-range flights. A B777 operating between Asia and North America will consume approximately 100 tons of fuel. A 5% burn variation will have a significant impact on payload and revenue opportunities. The only way to ensure accurate flight planning is to track fuel burn with an adequate fuel management tracking system.

Properly planning long-range flights can save airlines several thousand dollars per single flight by optimizing payload, route, arrival time, over-flight charges, alternate selection, use of decision point planning (reduced contingency fuel) or re-dispatch procedure, fuel top up procedure, centre of gravity optimization, etc.

A major issue affecting many airlines is the accuracy of the Zero Fuel Weight (ZFW) estimates. Because of these inaccuracies, dispatchers will tend to over-estimate the ZFW and pilots will add fuel since they do not have confidence in the accuracy of the ZFWs. Not only is extra fuel boarded but also the flight profile will not be optimal, further increasing fuel consumption. Properly tracking ZFW accuracy will help identify departure stations with the greatest variations from actual ZFWs.

Along with an accurate flight planning system, an accurate take-off performance calculator will improve safety and ensure the safe carriage of maximum payload. For accuracy, this system should be fully integrated with the flight planning system.

Airlines are reluctant to operate flights without selecting alternates. In North America, some airlines are planning a high percentage of their flights without alternates. The conditions under which airlines can operate without designating an alternate are well documented and provide a level of safety equivalent to any day-to-day operation when an alternate is used. The weather conditions have to exceed such a high limit that there is little chance of weather diversion. Two independent runways with appropriate approach aids must be available. Today, flights often operate to airports with a single usable runway and the alternate airport might also only have a single runway available. In this case, while it is perfectly legal, the landing opportunities are not any greater than the no-alternate option especially when the alternate airport weather is close to alternate weather minimums. In the case of dispatching without an alternate, the second independent runway basically satisfies the alternate requirements and alleviates the need to designate a distant alternate while maintaining a high safety factor. A modern fuel management system will permit the tracking of no-alternate potential flights by analysing the times such an operation was possible at an airport compared to the number of times the procedure was used. The cost of carrying unnecessary alternate fuel can be quite significant. Having an appropriate fuel management system will also help when monitoring the use of excessively distant alternates.

Re-optimizing flight plan profiles after departure is another option for minimizing delay costs. Airlines must have the appropriate tools to analyze the cost of late arrivals and re-compute the flight times once the flight is airborne. Developing such procedures involves several departments whose efforts must be coordinated to ensure all of the airlines activities are focused on minimizing delays. In the case where a flight has been initially accelerated due to specific operational requirements but where time is gained during the departure process (such as early push back or shorter taxi out time), the flight speed can then be reduced to minimise fuel burn. In some cases, connecting flights might also be delayed therefore reducing the delay costs and the need to accelerate the flight. To accomplish this, an airline must have the ability to dynamically monitor delay costs while considering all operational factors.

Dynamically managing flights requires a very professional and well-trained team along with adequate procedures, communications and alerting systems, which will keep key stakeholders focused on the operation. Airlines desiring to operate dynamically and efficiently must acquire advanced flight planning systems, appropriate communication tools and expertise to permit these operations.

Flight Briefer

Needless to say an advanced flight briefer system will go a long way to ensure that the most complete and up to data information is available to flight crews during flight planning. Timely information along with graphical display of flight track reporting points plus the ability to superimpose winds, turbulence report, significant meteorology, icing, cloud formation, oceanic tracks, and satellite weather display, is essential. Due to the dynamic nature of an airline’s operation, it is important that crews are able to access the most up to date information at departure time; otherwise, inaccuracies will result from change of zero fuel weights or excessive alternate fuel will be carried as the weather often changes rapidly. Winds and forecasts will be out of date and crews will lose confidence in the accuracy of the flight plan information resulting in the carriage of extra fuel. Having adequate briefing information is important if an airline wants to reduce the carriage of unnecessary fuel. Briefing information should be available via the Internet so that crews can access the complete flight plan information from literally anywhere in the world while away from their home base.

Fuel and Operational Management System

A Fuel and Operational Management system is an essential tool to manage a major portion of the airline’s resources, providing critical information and necessary statistics to efficiently manage the day-to-day operation. The system must be fully integrated to a communication and alerting system, which highlights to the users any variation from plan, and guarantees the integrity of the data. The fuel management system must be interfaced with all other operational systems and collect the most accurate data on a continuous and timely basis. The system must also be capable of monitoring the operational efficiency of key stakeholders such as Flight Operations, Flight Dispatch and Ground Operations.

Managing the specific fuel consumption of each aircraft in the flight planning system is essential if crews are to trust the flight plan accuracy. Otherwise, they will make their own corrections and carry extra fuel. On the other hand, if the burn correction factors are too high, excess fuel will be boarded on each flight at great cost.

Accurate taxi times are critical not only for predicting block time but also for boarding the correct amount of taxi fuel. Airlines that proactively manage arrival times will require accurate statistics on taxi times.

Accurate data is also required if an airline wants to take advantage of using the statistical contingency fuel. In addition, airlines wishing to use the decision point planning procedure (reduced contingency fuel) will have to demonstrate the accuracy of their flight planning system. Only after proper analysis (completed by the Fuel Management Information System) will the accuracy of the flight planning system be certified to qualify the airline for such a procedure.

The pilot fuel consumption can vary widely. Most pilots will admit that it is possible to reduce fuel consumption by applying various fuel saving techniques. Unless the airline has a sophisticated fuel management system, it will not be possible to track fuel consumption variations between individuals. Pilots, in the current economic environment, must be accountable in a similar manner to other managers within the airline. Properly tracking individual pilots will enable an airline to focus on proper training and sensitization. While fuel burn variation from one flight might not be significant, over an extended period of time it will be possible to establish meaningful trends between individual pilots.

The same trend analysis can be applied to flight dispatchers who’s role is moving from a clerical function to one of manager. Efficient dispatchers can save an airline many times their wages by focusing on efficiency and accuracy. Managing accurate zero fuel weights, selecting the most cost effective routes, optimizing the Cost Indices and arrival times, optimizing loads, selecting the most appropriate alternates and finally managing the extra fuel boarded are all factors that will improve the dispatcher’s efficiency. Tracking flight dispatchers’ efficiency and providing them with appropriate operational statistics will only be possible by using an appropriate fuel management system with advanced business intelligence capabilities.

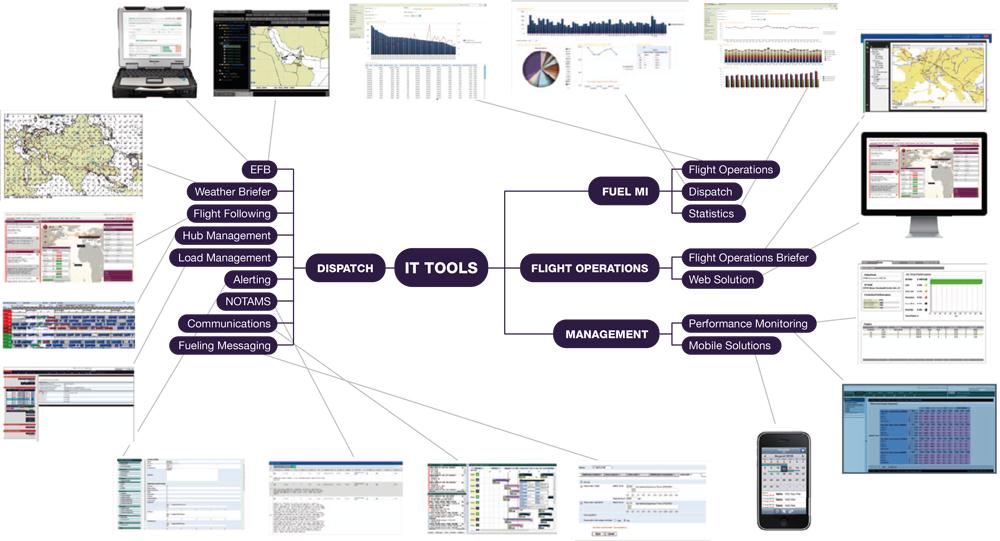

Figure 1: IT Systems and Fuel Efficiency

ACARS and Other Communication Systems

In today’s environment, it is extremely important to be able to communicate with aircraft during any phase of flight. The most common system used by airlines at this time is Aircraft (sometimes, Airborne) Communications Addressing and Reporting System (ACARS) although many other system are coming online such as Gate links, satellite links, 802.11, etc. Most systems have advantages and limitations.

We will focus on ACARS for now, although the list of data link systems is exhaustive and beyond the scope of this article. The point is that, if an airline is to operate effectively and collect accurate and timely operational data, the aircraft must be able to receive data automatically throughout the flight and store the data in a usable format.

Some airlines use ACARS very effectively, which greatly improves operational efficiency. In addition to receiving and sending important operational messages, ACARS can be used to upload flight plans, request weather information, load information data (such as wind information) directly to the Flight Management System (FMS), upload flight plan information, send messages throughout the airline’s organization or to other aircraft, communicate with Air Traffic Control and obtain ATIS information and clearances, communicate with Maintenance, update arrival times and so on; communications are critical for any airline wishing to operate efficiently. An additional important aspect of ACARS is the system’s ability to provide the data for a fuel management system as discussed above. Quality and timely data is essential for an efficient operation.

Conclusion

As can be seen, advanced IT tools will contribute significantly to improving operational efficiency, reducing fuel consumption and improving safety. This is in addition to improving customer service and minimizing the environmental impact of airline operation.

Comments (0)

There are currently no comments about this article.

To post a comment, please login or subscribe.