Articles

| Name | Author |

|---|

White Paper: Operational Data as a Global Business Asset

Author: Shaun Rattigan, Technical Director, Aviation Intelligence

Subscribe

An enterprise wide data policy will reap benefits for consistency, analysis and costs, explains Shaun Rattigan, Technical Director, Aviation Intelligence

Taking the Integrated Approach to Airline Operational Data

Airlines generally have historically taken a silo-style view of their various operational systems and data. Flight Data monitoring systems get used for safety analysis, journey logs for on time performance and crew data and so on.

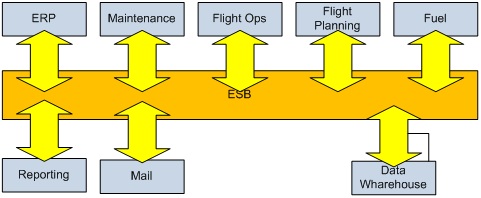

This is understandable, in today’s reactive and fast paced environment where return on investment (ROI) considerations, ever changing operating models and fluctuating requirements all lead to the tactical point solutions shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Building walls between delivery teams

The approach can lead to a bunkered view of operational data across the airline, with operational data from different departments only available to be utilized within the specific area where it was generated. However, with the emergence of the corporate IT department’s ‘standards’ and systems, and the requirement to improve the systems cost to revenue ratio, this bunkered approach needs to be reviewed.

Taking a more holistic view of the airline’s data will allow the business to make better operational and financial decisions. For example, try to establish what a completed flight actually consisted of and answers will vary from an explanation of the individual sectors to the overall report of the journey as flown by the crew – the block time cited will vary depending on which department is asked. And answers will reflect the sources of the data and the focus of the operational department.

A good example of this would be the OOOI times (Out of the Gate / Take-Off / On the Ground / In the Gate). With various sources including the journey log – paper or electronic flight bag (EFB) based – aircraft communications addressing and reporting systems (ACARS) and ground handling agents, it is almost impossible to get an agreed time for each point. Engineers tend (or may even be mandated) to use aircraft times whilst the crew system gets data from the journey log completed by the pilot. Discrepancies may arise but are not easily identified or acted upon.

Must the answer be a massive centralized system?

The concept of taking a holistic approach is not a revelation; IT departments have advocated it for years and there are many off-the-shelf solutions with which airlines can approach their systems from a wider data perspective. The issue with this wider systems approach is the initial cost of setting the systems up and the change of thinking required within the airline.

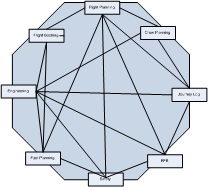

We have for years been propagating systems built with large numbers of point to point connections (Figure 2). These arrangements work operationally for tactical solutions but then, as systems change, the costs of changing and supporting the point to point links becomes increasingly expensive.

Figure 2

Once the airline needs to make an operational change or replace one of the programs in a point to point system, costs escalate massively due to the requirement to integrate data from the other programs in the system. Re-integration then becomes a major expense within the project, with the significant challenge and cost of modifying multiple interfaces from multiple vendors. It is the information stored in the data across the airline that will help to reduce operating costs: however, due to the disparate nature of the data held within the respective systems, accessing that data the issue. Reporting on an ‘application by application’ basis is straightforward but gives a slanted view of results. To use data effectively, an airline must look across applications to the wider implications of the data, not an application specific approach.

Approaching the data with a wider view we can start to make decisions based on this world view. This approach will also reduce the costs of supporting the multiple separate interfaces we currently use. Whilst the airline operates its systems with a bunkered approach, it will never really be able to make good decisions as each will be based on a specific viewpoint from a particular department within the airline’s operations.

Continuous Improvement Model

By moving to this wider view of the data, instead of trying to change all the interfaces at once the airline can start to implement systems that move it towards a fully integrated platform, thereby controlling the costs.

If we try and attack all the systems and interfaces in one go in readiness for or as part of a move to a fully integrated system then the task becomes a major exercise. By taking the Continuous Improvement approach, each system can be individually moved across and the business benefits realized in a matter of weeks instead of months or, in some cases, years. By identifying the individual systems and their payback the airline can actually move towards the strategic goal but build on the benefits in the short term.

This means that, for a relatively small effort and cost, the airline can start to see direct financial payback, system by system (Figure 3), while also moving the airline towards a more strategic framework.

Figure 3

Another advantage of this approach is that, as new systems are introduced, they can be implemented in order and made ready for the move towards a fully integrated platform.

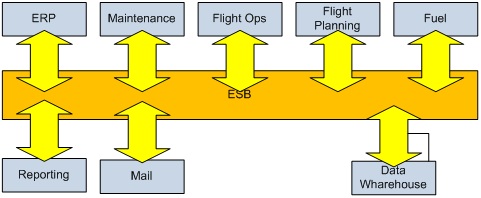

The aim of this paper is not to look directly at the Enterprise Service Bus (ESB) and its effect on IT systems: however, by looking at the data with a wider view, the airline can not only get some of the benefits in the short term but can also start to address the issues with point to point interfaces, ready for when ESB is more accessible and affordable (Figure 4).

How does IT feed into this process?

With the costs of supporting multiple complex IT applications and systems increasing exponentially, airlines are moving to more integrated IT systems and management with the aim of reducing these overall costs.

Figure 4

Expensive Change costs?

The cost of not taking a more holistic view of the airline’s data is apparent when one of the systems is changed; take the fuel planning system for example. Besides the implementation costs for the system, integration costs need to be addressed, ACARS, ETS scheme and other feeds need to be recoded and tested: and what about the costs of changing the ERP (enterprise resource planning) system itself?

No Silver bullet

The holistic approach to airline data requires airlines to have a clear strategic view of their data and how it fits together with regard to the different operational and regulatory or political requirements applying across their departments. The reality however is different: the ESB strategic concept is where some airline IT departments strive to be but issues of managing the day to day operational requirements and the costs of establishing such an integrated approach put them well behind the curve compared to other industries.

This may sound as if such an approach cannot be achieved without expensive data warehousing and an investment in ESB technology. In reality, some of the benefits can be achieved in a number of simple stages with a reasonably powered Database (SQL /Oracle) some storage and interface development work.

New implementations of systems need to be looked at in the light of this holistic approach. With EFBs (electronic flight bags), for example, it has always been difficult to create definable business benefits due to the high setup costs. If we take the holistic approach, then for the relatively low cost of some integration work we can very quickly get additional payback on the reporting and feeds to other systems giving added benefit and improved ROIs (return on investment) in weeks instead of months.

Standard Flights

Some people within the airline will argue that there is no such thing as a standard flight as there will always differences between the flight planned and as flown. Flight planning software, for example, goes to great lengths to optimize the flight plan, against expected winds, departure runways, routes etc.; and then pilots fly different routes and waypoints due to local conditions and ATC (air traffic control) requirements. This is not a criticism of pilots but does mean that the benefits of the flight plan are not fully achieved and, even worse, because we are not monitoring ‘planned vs actual’ we don’t even know we have not achieved those benefits.

Another factor affecting flight planning and with impact on the bottom line is the amount of fuel boarded. For instance, we plan, in the OFP (operational flight program), for an amount of fuel to cover taxiing (usually a fixed standard amount) but how often has the analysis been run to compare planned fuel use against actual? The data is there in the FDM (flight data monitoring) system.

Sometimes, additional fuel is uploaded to cater for contingencies that were not in the plan and, at the end of the flight, we find that fuel has been transported and the cost of the sector increased with no added benefit to the business. I should sound a note of caution here as there are always instances where, with good reason, safety is used as the argument for boarding additional fuel. However do we ever look at the actual figures and manage the risk accordingly or just accept the fact? If we have a way of mapping the disparate data (FDM, ACARS, flight planning, etc.) to points on a common flight path then we can start to use the data in concert as opposed each only being applied in separate analyses on separate data systems.

Where do we get the data from and how do we tie them together?

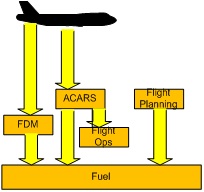

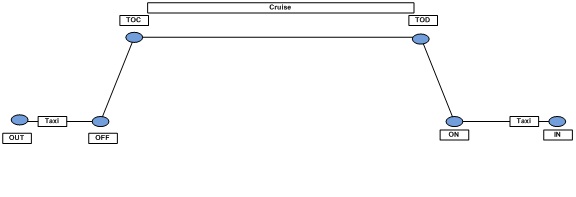

There are standard points and events during every flight and we can use these as the basis for reporting points. If we extract data for a given sector from each of the disparate systems and map them against the common points we can then start to build up a total picture instead of an individual application view (Figure 5).

Figure 5

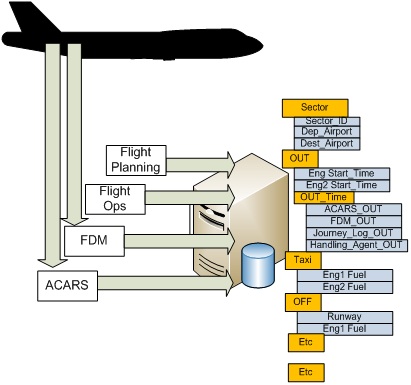

Why integrate?

The main advantage of taking a holistic view of data is that it allows the airline to provide a data platform that can then be used across the organization with a single data source to interrogate and provide the consolidated view of the data mapped down to an individual sector (Figure 6).

Figure 6

Now that the data related to each specific sector is gathered into a single database, the data comparison can be easily be undertaken, either by one of a number of off-the-shelf software packages or, even better, it can form part of a centralized reporting process to be used across each department throughout the airline. Business rules can be added to the system to ensure that for a given value there may be an alternative data source or quality rules can be put in place to ensure the data is within agreed limits, e.g. the technical limits of the aircraft.

Analyzing the integrated data expected for the flight as planned against the actual data generated will provide significant business detail that would have otherwise have remained hidden, such as the ability to analyze planned fuel against actual for specific airports or even down to the amount of fuel uploaded for alternates. Integration allows the business to analyze trends and not just individual sectors.

Fuel numbers, crew times and route information can all be analyzed over a period of time. Airports and alternatives can be analyzed to establish what effect changing conditions may create. In one instance it was established that there was a significant increase in fuel loaded when flying into one particular airport. This then declined after a period of weeks and the loaded fuel moved back to the average. The only thing that had changed was the introduction of a new alternate flight plan so that, where additional fuel had been loaded ‘just in case’, once the pilots were confident with the new alternate plan they stopped loading the additional fuel.

In another case, taxi fuel at a number of airports indicated that the flight planning system was using a generic amount for taxiing; when analyzed, this was found to be 50% over the required levels at some airports – it also indicated that, in some instances, it was under the actual amount used for particular runways.

By having the data in one source, various statistical techniques can be put into place and anomalies highlighted. It can then be established if the anomalies are one-offs or represent a longer term condition or trend.

Where do we integrate the data?

There is a growing tendency for application venders to build a level of integration into their specific applications. This is both good news and bad. Good news, if the business does not have or is moving to a separate middleware or ESB layer, because it provides a quick way of integrating data. However, as the airline grows and the range and size of the integration becomes more complex, then this approach would need to be revisited and a separate integration layer put in place. From a good IT perspective and from a support perspective, the integration layer should sit above the applications themselves and not be part of any particular application (Figure 7).

Figure7

One key area that will require a great deal of input from across the business is agreeing the business rules to be used within the integration layer as these will be crucial in gaining acceptance across the business. With the FDM system, for example, there may be a need to make entries in the database anonymous, so that pilots cannot be identified, to avoid union issues. This should not stop the airline moving forward as there is so much more data in the FDM systems that can be used for other areas of analysis without the need to identify the pilots.

Other market sectors have been using this concept for years both with their internal staff and with their customers. For instance, most supermarkets have now altered stock management profiles to reflect our cumulative shopping habits, generating significant savings.

Is there any low hanging fruit left?

Sales operations have improved their service to customers by analyzing the profiles of their sales teams and adapting their sales strategy to suite. Airlines are looking at how the bottom line can be improved particularly around fuel saving analyses but are not looking at areas like FDM, due to the issues around the identification of the flight crew. If we are able to use this data and match a particular sector with the flight planning system for example we can start to use the data intelligently across the areas.

By applying mathematical analysis to the data, various trends can be identified, giving savings from fuel and flight planning right through to the management of handling agents or ‘on time performance’. As the data is sourced from multiple systems with the application of relevant business rules, spurious operational data can also be identified; such as fuel logged as gallons instead of liters, fuel uploaded for alternates and taxi fuel built into the flight plan for specific airports. The application of business rules also allows the identification of automatic workflows so that, for example, a fuel report from the ACARS system may differ from the load sheet in which case the system can be designed to send anomalies to be addressed to individuals within the organization.

SVOT (single version of the truth)

A question often asked is, ‘which source of data is correct?’ The really unhelpful answer is ‘all of them’, depending on your viewpoint and the department in which you are working. This means that reporting for factors such as on-time performance, fuel management and flight planning may have no consistency across the business; one management report might contradict another’s figures. Try rationalizing the total flight hours recorded by engineering against flight hours from the journey log.

The aim of taking a holistic approach to the data is not just to create reports that agree with each other but also to use the data across the airline more efficiently. Some airlines use the FDM data just for flight safety and have not made the connection that there is a great deal of operational data in there that could be used directly for other systems. This is setting aside the possible requirement to make the FDM data anonymous so the pilots cannot be identified.

The process allows airlines to start using the system with other sources to build in business rules, to ensure quality assurance (QA), the handling agents OOOI times, or to compare planned as against actual fuel used at each flight stage. Direct fuel savings can be identified with taxi fuel requirements based on the average at specific airports. This also means that primary and secondary sources of data can be identified and the business rules put in place to resolve any gaps in the data.

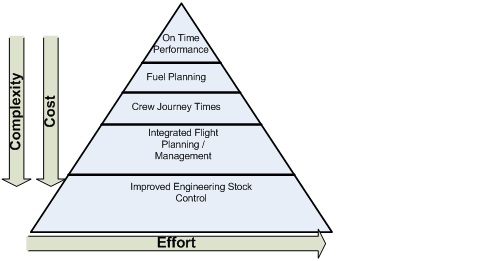

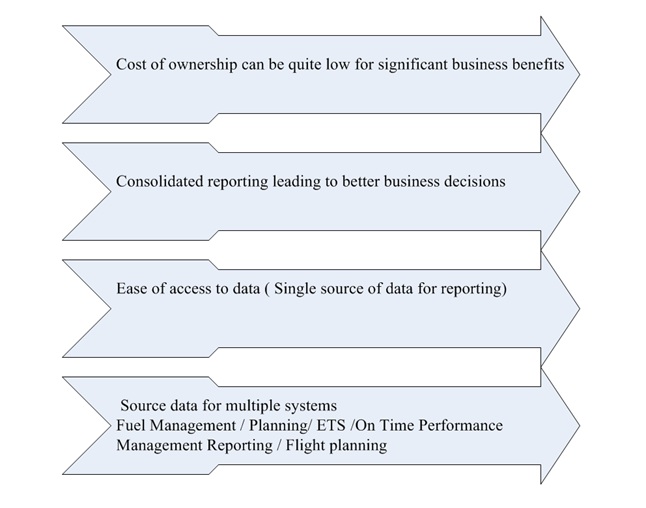

Tangible benefits

There are also a number of tangible benefits from taking this holistic approach to the linking of the disparate data systems and mapping them onto a single sector. The main ones are shown in Figure 8:

Figure 8

There are wide range of dedicated CoTS (Commercial off The Shelf) software packages on the market that allow reporting across different functional areas but these all require data; the single repository can be used to provide data to a wide range of systems from the single source, providing the airline with a simple in-house solution that can be used across the organization to improve reporting, ETS reporting, fuel planning & management, operational analysis, planning, on time performance and a range of other functions as well as providing a standard source of data to feed other systems.

Conclusion

The concept of driving the holistic view of operational data is not new; however, with the advent of more structured IT systems and strategy and the requirement to improve the bottom line, airlines and other sectors are starting to consider the benefits that can be obtained from taking this structured, holistic view of their data.

The long term move within corporate IT departments towards an integrated system approach and the requirement for more efficient and centralized automated flight operation systems will eventually help airlines to realize this wider view of their data. However smaller IT departments can still move towards this goal with smaller budgets and resource to provide a system that will not only give them short term benefits but should also move to a ESB structure fairly painlessly. Once the data is in a single source, the application of some very easy statistical techniques allows the airline not only to pick up anomalies but also start to identify trends.

Operational decisions and analysis can then start to be addressed, such as what effect flap settings have on the fuel used or even down to helping ensure the aircraft is configured correctly. One airline, for instance, noted that certain flights were fully configured for landing at 4,000ft when the standard operating procedures (SOPs) indicated 1500–2000ft. This had an effect on fuel used over a period of time and its identification also allowed the airline to highlight a training issue.

The holistic approach to their data will allow the airlines to start to gain the financial benefits without heavy initial investment costs. However, it is not the case that, with this holistic approach, airlines do not need to look at strategic tools, such as Enterprise Service Bus, that are currently used within other business sectors. The holistic approach is only a ‘starter for ten’, allowing an airline to move towards a fully integrated strategic solution which can be used across the business, including operations, and not just within financial management. The key words here are, ‘to move towards’.

As the software used and the reporting requirement across the business become more complex, and the requirement to maintain the links between the various systems becomes more costly, it makes greater financial sense to ensure that the procedures and systems put in place are easier to link so as to make even better use of the data across these various systems.

This holistic approach can reap benefits quickly, providing that the airline management understands the requirement for such an approach and that it is not driven from within any specific department but is addressed across the business.

IT is only a tool but, when looked at in isolation from each other, the IT and interfacing requirements of our complex systems can cause us to become blinkered and lose sight of the fact that for a business to succeed it must apply all of the business data available to make good operational and strategic decisions.

Comments (0)

There are currently no comments about this article.

To post a comment, please login or subscribe.