Articles

| Name | Author | |

|---|---|---|

| White Paper: How to ensure an effective fuel saving program | View article | |

| White Paper: The future of Operations Control | Christian Lambertus and Benjamin Walther, Managing Partners, Aviation Experts PCS GmbH & Co. KG | View article |

| White Paper: Future EFB Platforms and Hardware | Christophe Mostert, Managing Partner, M2P Consulting | View article |

| White Paper: The fuel budgeting complexities | Siow Litingtung and Simon Mayes Consultants, OSyS | View article |

White Paper: The future of Operations Control

Author: Christian Lambertus and Benjamin Walther, Managing Partners, Aviation Experts PCS GmbH & Co. KG

SubscribeThe future of Operations Control

Christian Lambertus and Benjamin Walther, Managing Partners at Aviation Experts PCS GmbH & Co. KG, discuss trends in development and usage of Operations Control Systems

In the airline business, operations control (Ops control) is the art of managing a preplanned schedule in the conditions prevailing on the actual day of operations; the objective being to fly this schedule with a minimum of changes. The typical view of operations control is of a process triggered when particular unscheduled occurrences force a change of plan for a single flight or group of flights, with Ops control then trying to regain the original plan as quickly as possible. In general, most controllers are expected to act only when the plan is threatened by ‘real world’ events. When there are no conflicts or disruptions, the schedule will be flown as planned.

This focus has shifted in recent years driven by economic changes and increasing competition in the industry. Whereas 10 to 20 years ago, controllers were administering operations largely in terms of stability, they now find themselves being asked to optimize operations wherever possible. In times of low margins and high cost pressure, the challenge for controllers is to maintain operational stability and, additionally, to save costs through optimization. Today, data streams of available information on flights are nearly infinite and this information can be used to the advantage of the airline in optimizing opportunity costs. Ops control is evolving and moving to become more than just a coordinator of the airline’s assets during production. It is gradually developing a role in the airline’s cost control policies and, in that sense, beginning to attract the awareness and interest of management.

These new requirements in the job profile of a controller need to be mirrored by parallel developments in the capabilities of Operations Control Systems (OCS), handling more information and supporting the controller in taking informed decisions. While stability has become a task for automated algorithms, the economics of operations and product quality are in the hands of and drawing on the experience of controllers. Systems are able to control standard adjustments in the schedule in response to outside occurrences whereas controllers can use the available data to manage costs and conduct individual adjustments with a view to optimizing operations.

But, judging from the history of operations control systems, it seems that this development was never foreseen. As already mentioned, the focus of OCS in the past was more towards ensuring a stable flight schedule which, in turn, drove the key functionalities of OCS to, for example, reducing crew changes, reacting to technical problems to minimize aircraft on ground (AOG) events, managing aircraft reserves and communicating with the cockpit.

These days, most optimization measures occur during the preplanning phase. Fuel optimization is the exception to this rule, being mainly controlled from the flight deck during the operational time frame. As soon as the operations time clock starts to tick down, the sole focus is on getting the job done. The main objective is still a smooth operation according to schedule: in Operations, ‘stability’ remains the magic word.

But let us come back to the infinite numbers of data available in an airline’s databases. What if Ops control was able to use this data and, as a result, was then able to optimize the operational schedule according to cost factors? It is true that, in most Operations Control Centers (OCC), this thought process seems, at first sight, to fly in the face of the credo of operational stability. However, this new mindset holds a potential for cost control at a stage in the process that most airlines have not yet identified as a possible source for savings. Nevertheless, the costs of optimization also have to be measured. Attention to stability should always play a role in the decision to optimize the operational setting. Therefore, optimization should only take place where it causes no change to service stability as perceived by the passenger, the end customer. With the vast amount of data taken from reliable sources, OCCs could become active centers for cost saving. The only question is: how to make the best use of the available information?

First of all, we should take a look at the new data which is available. It also has to be said, that the examples presented here are only an outline of the total opportunities that might be available.

One important data stream that will have been refined in terms of quality, volume and availability is information on handling processes performed at an airport, reflecting the status of a flight before departure. Any controller is able to turn this information, combined with his or her personal experience, into a measurement of probability. This is a huge factor in Ops control that can be increased in terms quality and accuracy by the enhanced level of information provided. It will be especially true for airlines that operate high frequency continental networks and have high aircraft utilization. Their operating model is based on using all resources to the fullest extent possible. Information about a flight’s ground handling status is valuable to the controller, who has to take care of operational stability at the hub during peak time, when the flight will arrive. Decisions can be made faster and earlier if the controller has the information on all available aircraft in nearly real-time and is able to build alternative scenarios as a counter measure to certain irregularities which might have occurred, or might potentially develop.

Large legacy carriers might have an advantage here as their assets, in terms of aircraft, have a slightly lower level of utilization, due to the nature of their business model. With these large fleets operating in and out of intercontinental hubs, the complexity is generated by the traffic mix of short and long-haul flights which are linked to each other, creating a network-wide dependency. Knowing in good time that the A330 in Miami has suffered a delay of 20 minutes due to the procedure of off-loading a passenger, will give the controller the time to immediately evaluate the situation of the upcoming flight and its impact on the network at the airline’s hub in Frankfurt. Whereas in the past this information was available to controllers mostly after take-off at Miami and only on receiving the timestamps that were linked to aircraft’s movements, they can now start examining the further development of the flight under ‘real world’ conditions. This will include a check-up on all critical components affecting this flight to determine the probability that the flight might make up the delay or whether it will bring the delay to the hub due to en-route weather conditions or an inbound arrival peak when approaching Frankfurt. In this way the controller can start preparing actions and recover operational stability earlier, but still with enough time to thoroughly consider cost savings according to the philosophy: ‘If I have to change something anyway, then I might as well optimize.’

With regard to our example specified above, it is also possible to include new data into the information flow of the Ops control system. Features like Google Maps or weather services can be taken from the internet and integrated into the system so that the controller has a common source for all information. “Our controllers were operating on four screens with three being used for the OCS and one was used for applications showing an internet browser with 37 tabs open and active during the entire time;” says Axel Goos, System Manger OPS Control System and Warehousing at Lufthansa German Airlines. He adds that, “by integrating the information into our new OCS, controllers have a central platform bundling all necessary information, making the process of elaborating a high quality decision much more convenient for the controller. The benefits are at hand: motivated controllers being eager to make the best out of the given situations with the tools they have.” Another way of putting this important argument is that you cannot repair a Roll Royce with a 40 year old, rusty incomplete toolbox you found in the garage under a pile of junk.

But, returning to our flight from Miami to Frankfurt: with the data on passengers that today’s check-in and departure control systems hold, controllers receive accurate information earlier. Integrating Check-in data provides information on the actual load. This can be a factor in decision making for flights at the hub, being fed by our Miami-Frankfurt flight. With the flying time still to be completed, it is now possible to trigger processes to sell, on the onward flight, the seat of the off-loaded passenger. Even if the time frame is very short, it reduces the likelihood of a wasted seat, however this seat is filled in the end. It might also be an opportunity to relieve an overbooking problem and reduce overbooking costs. Being able to sell such last minute seats on one flight per day in a large network such as Air France, Lufthansa, British Airways and the like are operating will, on 365 occasions, generate revenue that otherwise would be lost.

Granted, all the examples used are test cases working in theory, although the individual functions described have been proven in projects. Also, one should always keep clearly in mind that stability remains the main goal, and it should never be sacrificed for optimization. But, the new generation of OCS will have capabilities that can reduce the controller’s standard workload by use of automation. The capacity that this will generate can then be used to focus on optimization of operations to the benefit of the bottom line. These savings may not appear as huge amounts in any single case, but aggregating the volume of flights and the different saving potentials will lead to an amount of cost savings sufficient to justify the investment in enhancement and development of new OCS software, with a realistic and economically feasible return on investment for each airline.

The development of OCS is certainly one of the most complex processes for airlines. This is linked to the stability and availability requirements for OCS being much higher than with other systems. A system failure, wrong data or malfunctioning interfaces can lead to enormous problems and irregularities, resulting in tremendous losses on the bottom-line. It is also important to bear in mind the direct impact on passengers.

In reality, the development of OCS during recent decades has been at a slow pace. Most airlines operate stable systems, which have been enhanced with additional data but little new functionality. The implementation of major new technologies from other fields has never been on the agenda for system vendors and users: for instance, in the field of graphical user interfaces (GUI), many airlines still rely on outdated technologies. This is largely because user interfaces have never been the focus of development and so even major airlines are operating OCS based on the Motif GUI Toolkit which was first introduced in 1980. Notwithstanding that Motif was a milestone in graphical user interface development and very a powerful tool, GUIs in the wider world continued to evolve over the past 20 years. To draw a comparison with a personal computer; it is like working with Windows 3.0 when everything else is working on Windows 7.

Let us take a more detailed look at the developments of recent years.

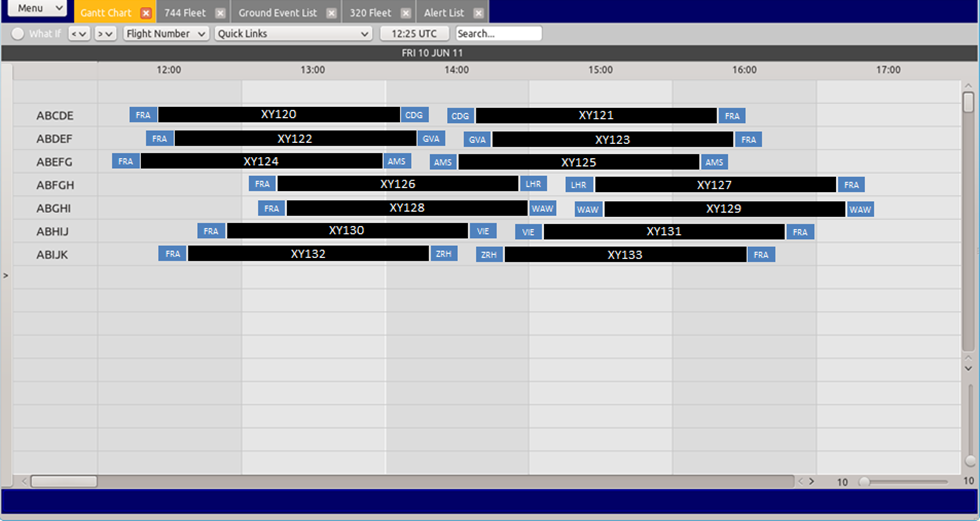

One of the main characteristics of Ops control is its ability to perform several tasks at the same time, especially when it comes to major disruptions. In the past a controller was limited to a single Gantt chart which made it very complex and time consuming to work on more than one problem at a time. The current trend is similar to that of internet browsers, using multiple tabs which are more or less independent of each other. A controller can build one scenario in one tab while, at the same time, focusing on another issue in another tab. Although considered as a simple enhancement by those in the industry, the usage of multiple tabs/Gantt charts eases the work of a controller tremendously.

Let’s again apply the comparison of OCS and internet browsers, where tabbed browsing was introduced as early as 1994; nobody is using a browser without that feature today. Indeed, Microsoft lost a huge market share because they were one of the last to introduce the tabbed browsing technology.

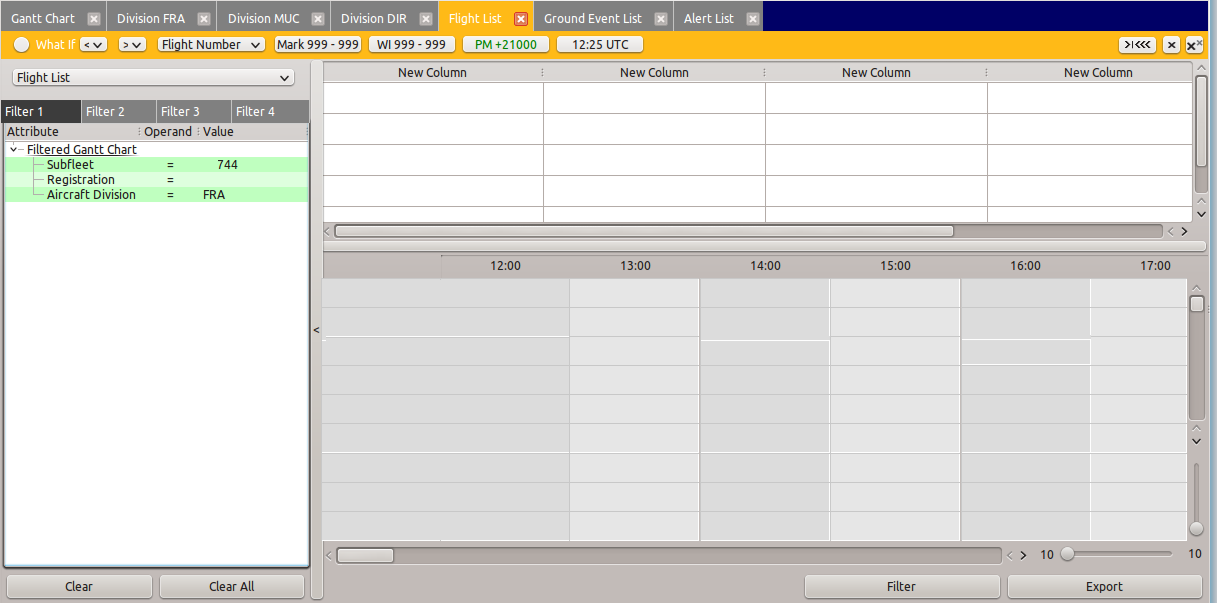

Beside the use of multiple Gantt charts, another important development is the integration of enhanced filter tools. In the past, OCS provided huge GUI interfaces which made it nearly impossible to work with. Similar to a lot of other software tools, the trend in OCS is now turning to so-called ‘Property Widgets’. Compared to traditional filter GUIs, the use of property widgets is much easier and faster, and the results can be shown in real time while the task is being performed.

Altogether, the development of OCS during the next few years will be very much driven by enhancements to user interfaces and an adjustment towards standardized systems. Controllers will no longer be prepared to accept difficult to use systems as they did in the past.

The complexity of such systems is reduced when the right balance between automation and decision support can be established. Automation, as the logical approach when it comes to process improvements, is a lever that needs to be discussed and evaluated. On the other hand, decision support philosophy keeps the responsibility and decision making in the controllers hands, by serving as a powerful tool to provide the right information at the right time in the right format.

Instead of focusing everything on GUI enhancements, a lot of effort, during recent years at both system providers and airlines, was put into the development of decision automation. This included automation of specific problem solving processes as well as the optimization of the complete flight schedule. The latter is definitely one of the most complex automation/optimization problems in the industry.

With regard to the fact that increasing amounts of detailed information are available in airlines’ databases, one has to ask the question how this vast amount of information can be applied towards better Ops control. There is certainly scope to increase the quality of decisions made but the question resulting from this conclusion is how this quality is measured. Are airline managers still aiming to reach the perfect state of operational stability as their only goal? Or do new technologies enable controllers to optimize customer satisfaction and reduce the impact of OCC as a pure cost center to instead contribute to the airline’s bottom-line?

To cope with the economic challenges of operations control, the focus of developers should turn to areas that have been sacrificed on the altar of perfection in stability and functionality. And a first major consideration should be improvement in terms of user friendliness. New GUIs with graphical enhancements, in line with common IT developments, will facilitate greater ease of use and access to information. In the optimal case, users will find a commonality with their personal computers at home and be intuitively able to navigate through the system to the required function or information. This will reduce the time needed for a task and stress levels generated. Users can access more detailed information by choosing multiple perspectives to look at the same issue and come up with an individual solution to the problem.

Enhancements in the area of Ops control will be driven by the new perspective on cost optimization in the operating timeframe. Therefore OCS can be improved by applying automation measures to resolve ‘standard’ irregularities and deviations from the plan. However, to achieve the status of being able to optimize operations without harming operational stability, OCS need to evolve into information platforms for their users, bundling all available information. The success for IT vendors will be in the configurability and flexibility of the OCS to sort, display and link information in the way the user requires. As for the airlines’ part in the development of new OCS, they have to be aware that, as in other fields of the business, no development comes without investment. It also requires a change of mindset to establish the new philosophy. Then one thing is certain: Ops control will be a successful cost-saving center, when users are provided with the right tools.

Comments (0)

There are currently no comments about this article.

To post a comment, please login or subscribe.