Articles

| Name | Author | |

|---|---|---|

| Why does the industry always start projects in the middle? | Michael A. Bryan, Principal, Closed Loop | View article |

| Rostering Optimisation Made Simple | Dean Stewart, Managing Director, Betley Bridge Consulting | View article |

| iPad/Tabelts in Flight Operations – Trend or Solution? | Paul Saunders, Operations Director, Conduce Consulting | View article |

| Integrated Operations and Hub Control Management | Gesine Varfis, Managing Consultant, Lufthansa Consulting | View article |

Why does the industry always start projects in the middle?

Author: Michael A. Bryan, Principal, Closed Loop

SubscribeProject Management: Why start in the middle?

When there is a project to be carried through, Michael A. Bryan, Principal at Closed Loop suggests that starting at the beginning is best

At the MRO the Americas Conference in Phoenix last May, Scot Kirby, President of US Air said that airlines had to continue to identify and remove costs from the business. It was a matter of survival. The sentiment is of course valid, but to what point? Kirby went on to note that unrelenting pressure to remove costs put the industry on a race to the bottom with ‘inevitable’ results: a race that no one could win; yet we were all in it. What happens when there are no more costs to remove, when the effort to save the next dollar costs more than the dollar it is seeking to remove? The answer is of course revenue. Mr. Kirby went on to trumpet ‘ancillary revenues’, suggesting they were now a “permanent fixture of the industry”. Unbundling, he said, was here to stay. However, simple unbundling of the ticket and recharging more for each component has already raised consumer ire.

In a recent paper, L. E. K. Aviation and Travel Practice boss John F. Thomas discusses the value and the necessity of ancillary revenues. He points out that some are, or may be, unpopular, particularly those the embattled consumer has forever associated with the price of the ticket (Executive Insights Vol IX Issue 3: Creating Ancillary Revenue Opportunities, Rethinking the Airline Selling Proposition). Indeed. At the above conference, pushback against ancillary fees was cited by the CFO of IATA. His view, inter-alia, was that the silver bullet had become a poisoned chalice. For this conference, the cost of transporting display material, even in this era of ever lower fares, was pushing folk, particularly groups, back to their cars. Conference statistics, according to figures quoted in speaker presentations at the function, was that those inside a six-hour drive from Phoenix got in the car.

Of course, John is right on several fronts. His article addresses strategies for reversing the slide of yield and collapsing margins. For too long the focus has been cost competition at the expense of attention to the revenue side of the profit and loss (P&L) account. However, the article’s title provides further insight – the Executive Insights banner is addressed squarely at the C-Office strategists and while a lot is not written in the article, a lot can be inferred from John’s words – it is one strategy for airlines to consider for changing the business model but its success will all be about how it is implemented.

So, here we are in an unwinnable race to the bottom on cost control, supplemented increasingly around the world, with unpopular, poorly implemented revenue tactics that have yet to gain broad traction and are being avoided in an ever-widening radius. Airline management is hoping that, if one brand introduces an unpopular fee, the potential exodus of custom will be plugged because everyone will eventually do it to get a share of the new revenue, rather than seek to differentiate on price, value or utility.

The industry is nearing the bottom of the curve in its ability to shave further costs from the business without affecting its ability to operate. The so-called, low hanging fruit – the easy targets of waste and slack within the organization have, largely, been removed. On the revenue side, ancillary revenues and unbundling of fares are being tested but consumers are letting the industry know there will be a limit on how far that tactic can be pushed. Particularly when they are enforced by less service oriented outcomes. Picture the self-service kiosks that whistle and wail when your bag is a gram over the limit. While intended to ease the queuing and pain at airports, actual implementation has been less than perfect.

What’s left? The differentiator requires looking inward, to the business, not over the fence at what others are doing. It is called innovation and when openly discussed with industry management there is tacit agreement that it is a key tool necessary for the very survival of some: but, for all its necessity, it is deemed too hard. Why? for several reasons.

The L. E. K article poses innovative ideas, strategies for an airline to consider; the latest MRO and operations systems such as electronic flight bag (EFB), promise and can deliver, step changes in business efficiency. Yet, organizations still struggle with them because many (most) are not successful at making the transition from strategic ideas to successful implementations.

The tool to move strategy to practice is called a project (or program – but let’s stick to one term and infer both for the rest of the article). There is an abundance of authoritative and academic material available in the public domain regarding the science and art of project management. Yet, industry wide anecdotal evidence supported by embarrassed and hushed admissions, in quiet corridors of airlines all over the world, suggest that the industry is generally not pleased with its success rate for developing, managing and implementing (delivering) projects, putting us all in a Catch-22 cycle of having no appetite for innovation for the reason that we are unsuccessful at consistently delivering the very change that is necessary because we get it wrong, or not quite right, most of the time.

The problem is exacerbated in innovation or high-technology programs because excitement about some sort of widget tends to focus attention on that, at the expense of careful, rational and strategic analysis at the project level. The result is too often a ‘square pegs in round holes’ approach; forcing on ingrained business processes, procedures or policy, something that does not quite fit. Personal, departmental and, sometimes, organizational pushback occurs to the degree that the intent of the strategy or project, its potential value and the business case all suffer. Cracks develop in the project and it becomes bogged down in organizational issues, scope and functional disagreements, wish lists, etc., that send the project into a doom loop spiral of constant requirement changes, change requests and the value debate, resulting in project failure in some cases but certainly costing money and time well in excess of the original estimates.

Dollar values aside, the cost to the organizations involved in terms of lost relationships and opportunities have long term detrimental effects on the industry’s ability to learn, innovate and grow. In an industry where commentators are increasingly promoting the premise that the industry needs to re-invent itself for survival in the volatile landscape in which it exists, consolidation of the organization into a united whole, built on strategically important relationships, is vital for the success of the pan-organizational, transformational programs that will become more necessary as the pace and depth of change accelerates.

Right about now, I can hear the cries of indignation from those who have closed successful projects. Congratulations, you are of the fortunate few. Asking the question another way; how was the business case evaluation after final implementation? Does it look like it did when it was sent to the VP Finance, CEO or Board for approval? When we discuss this question with airlines, there tend to be only two responses: “No, it doesn’t,” or, “we don’t know.” It is rare indeed to hear that everything went as foreseen. Projects are simply not like that. Mostly, airlines have the new thingummy up and running and simply don’t want to know what it really cost in terms of effort and money. There are the next crises to solve just now.

Discussion usually surfaces about ‘oh, we added this and that or changed tack here and there and it didn’t quite turn out the way it was planned’. The reality is, few rarely do and for larger, technical, innovation and change projects it is almost an impossible dream. Nearly always, they cost more than the planned and approved budget. Why?

Whether or not the project or program is eventually successful, the cracks and additional costs add to the perception of difficulty and lack of success delivering with projects in the industry. These additional costs, for very little, if any, additional utility, are a burden or a ‘premium’ on projects that cause organizations to retreat from the very solution to what ails them. A mantra of ‘simple is best’ develops – whether it is implementing some new widget or fundamental business change such as those suggested by John’s article above.

They become used to the fact that additional funds are almost always necessary, so confidence falls in the ability of the organization to deliver successful projects: the premium is added, here and there, as the project is developed, almost as a type of risk mitigation. But simply adding to the financial hurdle, by making the business case harder to clear, only reduces risk by ensuring projects don’t go ahead in the first place, the organization is, in reality, no better off. The problem becomes a cyclical one of great innovation not being able to clear growing financial hurdles that become necessary for approval, not the financial hurdles necessary to test the viability of a project. Investment is curtailed, the cost of capital rises inexorably, and the cycle is complete and more difficult to break. Organizations become averse to future programs, which results in organizational stagnation, or worse.

Discussion suggests that the industry premium on projects is somewhere in the order of 150% to 250 – alarming figures. In the same hushed manner as they were provided to the author, the sources of these estimates cannot be provided here. However, as a program is analyzed for potential benefit, one must ask what does the assumption of a premium of these magnitudes or, come to that, any premium when it surprises the business, mean as the organization assesses later programs? What does it mean for the business case when these premium assumptions are added-in?

We end up with impossible to achieve, unrealistic financial requirements such as projects must ‘payback in 12 months’ while demonstrating that they return at least the cost of capital over some arbitrary cash flow period. For strategic, pan-organizational change, is 12 months really realistic? It is highly unlikely. Consider those projects that can be squeezed into a 12-month turnaround. How likely are they to be well integrated with the business and its systems, processes and overarching strategy to really resonate to the bottom line? Of course it is true that small, narrowly focused projects, may be appropriate to a critical issue in the business, but the ones that are really going to change the direction or future state of an airline will have many technical and personnel dependencies.

Exacerbating the difficulties with the cycle described above, most organizations have adopted a single Project Management methodology to drive the process for any project to follow. Methodologies such as the System Delivery Method, 8 Step, Agile Development, Iterative and Incremental Development, Rapid application Development, the Spiral model and the Cascade or Waterfall methods are all project cycle models that airlines adopt to guide the project process. But, are they all relevant? Each of these has its strengths, but also weaknesses[i] [note the footnote here – see end of article for the notes]. Just like the focus on the widget alone, it is also true that many of these prescribed methodologies are less than suited to the projects on which they are unilaterally imposed. These methodologies primarily relate to software development, not the implementation of new ways of business.

The issue often arises from the notion that projects that have an IT component ought to be project managed by the IT department. It would be an accurate observation to suggest here that most transformational projects, particularly those that are organizational in nature, have an IT component; probably a significant one. In many attempted implementations, the process tends to become the focus. Business drivers, desired outcomes and organizational strategy slip to into the background in the same way as focus on the widget can cloud the problem it is trying to solve.

Looking more deeply, examination tends to demonstrate that projects become viewed as a strategy and then organizations bind the project to a fixed model of how it should be done. Taking EFB again, the emphasis has grown over time, for good reason, that it should be viewed as an IT system, not an avionics system. There are significant pros to this argument, but also quite a few cons. This debate is still continuing and in the opinion of this author, neither position is correct.

Considering the process as a whole; someone gets a great idea – from a magazine like this one, a trade show or the latest great idea for rearranging deck chairs. Presentations are made and papers are written to get it moving and excitement builds. Analysis is undertaken, but it focuses on what the organization will look like when the widget (or new way of being) is part of the day-to-day routine. Requirements tend to be developed to suit the widget. To ensure it is all done properly, there are the project standards mentioned earlier, the way that projects will be managed in an organization to ensure due process is followed. Both the focus on the widget and the one-size fits all project cycle formula mandate ignore a vital aspect; not many strategic ideas are the same and neither are the projects that are necessary to guide the journey of implementation.

These issues are symptomatic of jumping into the project process in the middle. Taking the proverbial solution (the widget) and going to find a problem to which it relates or, worse, imposing a solution on the status quo. At the same time, a ‘due process’ is imposed to ensure the widget (or business change) is implemented in accord with an IT process that was designed with something else in mind. Many industry projects suffer from ‘cart before the horse’ syndrome.

They are squarely an issue that defines the way the organization develops and implements strategy. Remember; projects (and broader programs) are just the tools by which strategy is delivered, particularly where the strategy involves any change to the status quo of the organization. So, the importance of how the project is defined and how a strategy integrates with the organization’s broader strategic direction becomes a key determinant in reversing the trend and realizing more project successes within the industry.

By way of example, let’s do a walk-through of, say, an EFB program implementation, although it could be any change program for the organization. Where does it begin, with whom? What is the usual process for realizing it within the organization? What comes first, the widget (in this case, the EFB) or an examination of some business issue to which EFB may form a component of the solution? What process might be followed to make sure everything is considered.

In too many examples, the process is one of picking the box and trying to implement it forward. This process leaves behind the necessity of making sure it fits a problem that exists in the organization and that it is assisting some higher level strategy. The process becomes laden with other issues as it moves forward too. Does this choice of box and the applications that will be deployed really fit the organization’s needs, or answer some problem? It is here where scope creep, that insidious nagging that something has been left out – so let’s make sure it is in – occurs. This happens because proper analysis was not completed. The euphoria and enthusiasm takes over. It is not an isolated occurrence. By way of example, let’s look at two similar and real projects.

The first is a long way in to the implementation process. Hardware and software have been chosen, but with little consultation and in the absence of a rigorous comparison against a set of business, functional and non-functional requirements to ensure business fit. As aircraft deployment approaches, work is taking place to ensure regulatory readiness. Consideration of normal and contingency procedures is taking place, very late in the process and, with it, a discussion about possible back up procedures or systems. During that discussion it is realized that the deployment of EFB will potentially lead to an increased workload on some of the types destined for fitment of the system. Discussion has since become focused on a software functionality wish list – further scope change requiring redefinition of requirements. This is a revisit to a much earlier time in the project and, at this juncture, will potentially add considerable further expense. It is not the work necessary to ease the implementation of the system.

Additionally, discussion about back-up scenarios turned to a debate about another device to provide a back-up to a back-up. The suggestion being made now is that the back-up device might be issued to all pilots and could mean that some aspects of the initial hardware and software specification will not now be required. This aspect is confusing the project further as it approaches a vital milestone.

The second example illustrates a project where a single department within an airline is pressing for the deployment of a personal issue device to its pilots. The premise being that with this widget, EFB is no longer a necessary consideration. The reality is that this conclusion is not a simple (or necessarily sensible) one to draw, however it exemplifies the example where requirements are written to suit an outcome, rather than as a part of a process that will to lead to one. The widget has been chosen and the Statement of Requirements (SoR) requires suppliers to deliver applications that will run on the device but at the same time, are compliant with standards and already deployed systems that cannot run on the device. Significant expense will be incurred by the organization while adjustments are made to existing infrastructure to support a particular device, but adding little value to any other aspects of the business.

Certainly there is a business case structured around the device, but because the implementation it is not well integrated back into the business, the reality will likely be that one department saves, while others struggle to cope with the necessary changes to required process. While not an inevitable conclusion, typically these arrangements save expense in one department while adding to effort and expense in other departments, i.e. it costs the organization more overall.

Quite simply, focus on a widget, however it might be incarnated, and prescribing a one-size-fits-all approach to the formula for implementation, does not work and these two issues are symptomatic of the problems surrounding projects in the aviation industry.

To address these issues and make a positive turnaround to our project success rate, a reusable, repetitive manner of structuring our projects that provides a higher likelihood of success, a template or methodology, is necessary, but it must be appropriate to the type of projects and the environment to which it relates. Following a proper project analysis, we can then choose the most appropriate parts to fit a given solution rather than the one-size-fits-all of the single IT methodologies. In other words, we need to develop a system that is designed to suit the steps required for changing the business from one state of being, to another. This is not as simple as it sounds because most projects are trying to solve many different issues.

Consider then a system analogous to aviation and with which I am sure we are all familiar: standard operating procedures (SOPs) are the bedrock on which aircraft operation is based. The alternative is chaos. With no clear delineation of who was needed or required to do what and when and moreover, who is in charge and where the boundaries of authority and accountability reside, the industry would not be able to boast the safety record it rightfully trumpets. SOPs vary by aircraft type because every type is different. That is, they are designed to optimize the operation of the particular equipment within a particular airline environment.

SOPs also serve to support the crew as a team, defining roles and responsibilities, accountabilities and recognition, and they are a safety valve, ensuring early recognition of things that might not be normal or that require attention or action in a particular situation. So too, must the project template be appropriate to the requirements of the scope, quality and timing of our change requirements. It becomes easier to see why each project might be different.

Similar to the project Work Breakdown Structure (WBS) let’s now consider the business steps necessary to ensure our project has all the necessary pieces so that it can more likely conclude successfully or counter the reasons for failure.

First, let’s examine some reasons for project failure. In no particular order and also widely available in the public domain, these points suggest reasons for the 70% failure rate in managing change:

- Lack of analysis of precise business needs.

- Lack of definition of business benefits.

- Failure to identify tangible deliverables.

- Too much attention on the end goal, rather than the journey.

- Lack of accountability provided to the Project Manager.

- Poor leadership on the part of the Project Manager.

Recognize any? When our organizations focus on the outcome and do not provide the people in the team the proper role definition with commensurate responsibility and authority, we are inviting failure. An unwillingness to provide the team with basic accountabilities suggests the organization is not fully behind the change and failure to understand the reasons for a proposed change, the benefits to the business is an absolute recipe for failure.

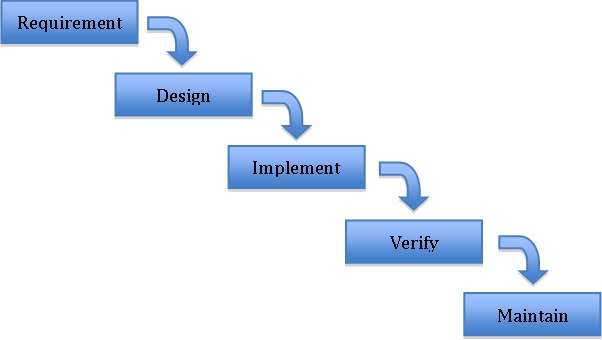

Often, the ‘start in the middle’ syndrome is driven to a degree because of the methodology chosen by the business. Consider an iteration of the waterfall model:

This model invites jumping in at the requirements level and ignores to a large degree, necessary examination of the proposed strategy and implementation project before this point, that is, concept and definition. It also exemplifies a shortfall in this type of model for many innovation implementations. It is very expensive to climb back up a step if requirements change once the next step has begun. Indeed, project management texts convincingly demonstrate how rapidly cost, risk and time escalate as changes are introduced later into the project.

So, a framework needs to be developed that recognizes the key requirements of a projects ability to manage several aspects moving an organization from one state, to the next.

There is the technical aspect. What has to be done to implement the widget, whatever it is? These phases are variously identified but generally follow the following outline:

- The idea! With little or no structure, this is where the idea happens; where the light goes on above someone’s head. Discussion begins and usually this is where decisions are made about jumping right in. Slow down, consider moving on to…

- … Concept and definition: this is where the project is aligned with the organization’s priorities, strategic objectives and alignment requirements. This phase helps ensure that the organization is going to be behind the project. Deliverables are brainstormed, alternatives are considered and initial financial with other tangible or intangible benefits are identified. Potential stakeholders are engaged.

- Planning: in this phase, the project structure is decided. The deliverables, back office process changes, training and IT needs are analyzed. Project Management and reporting structures, personnel availability and assignment, roles and responsibilities are decided. Regulatory authorities (if required) are engaged in this phase. Project and new business process risk analysis is completed here. An initial timeline is developed. Management are required to ‘pull the trigger’ in this phase.

- RFI / RFP: this phase forces the organization to develop some boundaries and detail to their requirements because they have to be articulated to and understood by a wider audience. A significant consideration in innovation and projects with a high technical component is the collective knowledge of the industry at large. Who is doing what? What are the options available and implementation options that will suit the identified need? The RFI process provides a market analysis of suppliers and leads the organization to appropriate demonstrations and discussions with suppliers who are highly likely to be able to provide an appropriate part of the solution.

- Proposal analysis: this phase helps the organization reassess its requirements. Are some too expensive? Which will provide the most organizational benefit? This is where weightings are appropriate to level the playing field. Stakeholder involvement in the analysis phase ensures buy-in. Detailed costing surfaces during this phase, particularly if the requirements were sufficiently detailed.

- Supplier selection: negotiation of favorable terms and conditions occurs in this phase. The importance of this phase in the relationship between the preferred supplier and the company cannot be understated. This relationship will be where the success of the project will be forged. Differences between company and supplier imperatives like Legal and Terms and Conditions must be ironed out in this phase in a professional and ethical manner by both sides. In this phase, a joint development plan will be constructed to integrate into the company project plan and final adjustments will be made to requirements if there are any supplier dependencies.

- Project implementation: this is where the rubber hits the tarmac. The major body of work starts here. A final review and confirmation of the project plan occurs here. Final adjustments are made to the business case and the assumptions therein are confirmed and signed off. Any regulatory path should be finalized here. A review of the risk management status of the project should be undertaken to confirm earlier assumptions. In partnership with the supplier(s), testing plans should be developed to underpin the implementation assumptions. By now, plans that will be parallel to and underpin the technical implementation to ready the business for the changed way of being and communicate the changes broadly to excite and engage the organization should be complete. Documentation requirements should be identified and agreed. The plan now gets moving.

- Operational readiness and program finalization: final regulatory approval occurs in this step. Implementation phases if necessary are decided and implemented against the plan. Importantly, this phase includes a post project review to learn for the next time and audit the assumptions against reality and the accuracy of the business case. Closure documentation is completed.

As can be seen from the last seven steps, there is a lot to consider and importantly there is a great deal of work up front, before the project starts costing real money. It is in these steps where the battle for project success can be won or lost. It can be seen, as one examines the above outline, selecting the widget (or the supplier) and back-filling requirements to suit, or having no up-front requirements at all leaves a lot out of the process but does not really short cut it due to the elevated levels of risk to the project and the business in poorly developed strategy implementations.

While it appears at first glance that there is a significant overhead to get through before the rubber hits the tarmac, investment in the process will yield successful projects more often, which will cost less in the long run. Think of the cost of failure, or not quite getting the outcome that was assumed, when rework has to be done to get it right: particularly when the business invests in change for survival and it does not work. The money is spent, there is no benefit and it is harder to get approval next time because the premium applied to the failure just got bigger. The benefits of investing in an appropriate process become clearer.

While the process may seem daunting the first time, think of how a learning organization will adapt. It will come with less effort next time and the time after that. Consider also that there are a number of organizations in the industry that can assist you to structure this type of approach and coach you along the way.

Success in your projects is vital. Organizational confidence increases, the premium reduces and those changes you once thought impossible to clear the hurdles become possible. Innovation, in the form of properly implemented programs like EFB, MRO systems and many any other business opportunity strategies are now possible. The organization becomes less averse to projects heralding change because they can see positive benefit in adapting with success. Successes breed new thinking and a new, positive cycle is established. And your organization thrives.

Footnote:

[1] Rapid, agile, spiral methodologies are not suited to projects where significant infrastructure, such as EFB hardware and installation is required as part of the deliverable. It is too expensive to revisit these types of developments in an iterative fashion.

It is opposite to the cascade method, where all decisions that can be taken are made before moving to the next phase of a project. This approach also has it’s downsides such as ballooning project scope, long timelines and technology creep.

Comments (0)

There are currently no comments about this article.

To post a comment, please login or subscribe.