Articles

| Name | Author |

|---|

Will Trajectory Based Operations (TBO) usher in a new way of working? PART 2

Author: Michael Bryan, Principal, Closed Loop

Subscribe

Viewed from the airline perspective, Michael Bryan explains how Trajectory Based Operations, has the power to change the industry if we have the foresight to grasp the opportunity and learn from the past.

In part 1, we looked at the challenges facing commercial aviation and suggested a future that could be achieved if the sector is prepared to be bold. In this part, we’ll look at Trajectory Based Operations, the technologies that accompany it and how it could work.

Trajectory Based Operations (TBO) has been identified, conceptualised and designed to provide the mechanisms to keep the industry moving. Its success will rest on buy-in by every stakeholder in the customer journey ecosystem. As we step through its key objectives and operational nuances, think about how it’s going to change the way you do things, and whether it looks like the science fiction of earlier.

TRAJECTORY BASED OPERATIONS

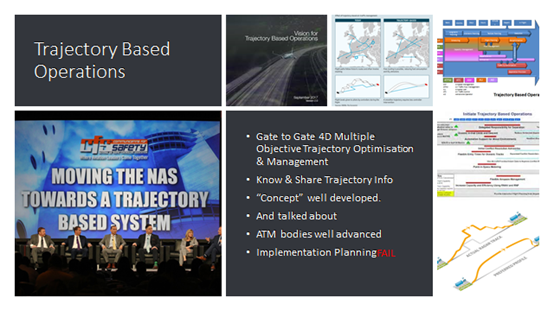

There’s been a lot written about TBO, and it’s out there for everyone to see; so, this article will highlight a few key points to raise the tempo for airline Ops departments and to get them thinking. The high-level objective of TBO is game-changing for the industry if it can be achieved. While its concept is about making room for growth, its component tenets drive significant efficiencies for airlines if they are smart enough to grasp them (Figure 14).

Figure 14

Gate-to-gate, 4D trajectory management will mean just that. The flight plan will no longer be just ‘paperwork’ required to get airborne, and then requesting ‘direct to’ here or there, trying to shave a minute or two. Or for ATC to pick you off a SID (Standard Instrument Departure) and send you ‘direct to’ somewhere you don’t expect and, perhaps not even on the flight plan you filed in the first place. The flight plan and its iterative evolution in terms of route, altitude profile, speed and time will be sacrosanct.

TBO achieves its objectives by everyone sharing almost everything with everybody, and universal data exchange will be crucial to its success. Those with long memories will remember the epic failure the last time the industry tried that. The concept is highly developed, even down to how the air around the globe will be sliced and diced, and how conflicting trajectories will be identified and managed from long-term schedule analysis to day-to-day and in-flight trajectory re-optimisation. Note: the term is ‘managed’; not ‘controlled’. ATC, Dispatch, Operations Control (NOCs) and the pilots will need to exist in a symbiotic relationship requiring three or four-way data exchange for the duration of the flight and before. The connected EFB will be crucial to TBO, and so will new smarter, intelligent, integrated and workload reducing applications, a contrast to the paper-centric paradigm that many applications follow today, will be fundamental to the success of TBO.

The concept is mature and is discussed often, but predominantly at very high levels of the air traffic management sector: the take-away is that very few airlines are talking about it yet. ATM organisations like Eurocontrol or NATS and the FAA are well advanced in their thinking about how it’s all going to work – for them.

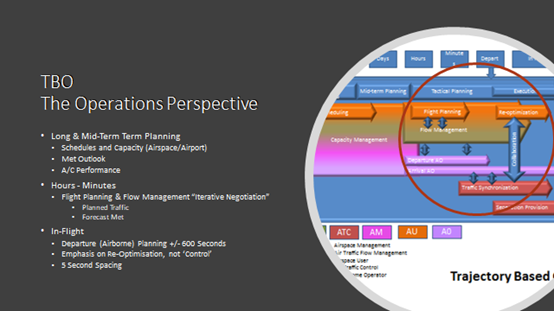

As usual for the industry, implementation planning at the airlines is lagging for too many… most of the TBO component programs. Delving deeper, long and mid-term plans for TBO (Figure 14) won’t carry any earth-shaking revelations.

Figure 15

Most airlines publish their schedules a long way out for essential reasons. Airline’s schedule data will be analysed in the context of every other airline’s and mixed with additional information like airspace closure for events or military use. Statistical weather and aircraft performance data will the thrown into the mix; iterative calculations will start running a year or more in advance to determine where long-term planning drives hotspots of capacity constraint and potential conflict. So far, so good, there is nothing too difficult.

Focusing on day of operations, however, things get different, quickly. The current ‘file and forget’ submission of flight plan procedure is about to change and become a more iterative process involving several players. Instead of Dispatch submitting the flight plan and leaving Air Traffic Control to sort out the aeroplanes, TBO will require submission of your flight plans, along with those of everybody else into the TBO system. Flight plans and their trajectories in terms of route, altitude profile, speed and time will be crunched and initially, and as far as possible, de-conflicted before an aircraft leaves the gate. Authorised trajectories returned to airline dispatch centres could include the original flight plan, the original flight plan with some restrictions, or a completely new trajectory. Of course, Dispatch can reject and re-submit, but can you see how recursive that could become? It doesn’t end there: Eurocontrol documents show that the number-crunching currently requires hours to solve the trajectories for operations covering just one hour over a part of Europe during the summer peak. Imagine that on a more global scale.

Closer to home, Dispatch, Ops, the pilots and the fuelling contractors have different issues to solve. What happens if the authorised trajectory is materially different from the plan and changes in speed, flight level or route and cannot be accommodated by the fuel that’s already on board? What about getting the new flight plan to the pilots possibly as late as minutes before departure if changes in the submitted flight plan have been necessary? Many thoughts will turn straight to technology, which is undoubtedly cool stuff, but that’s the easy piece. What’s not simple is the human factors alarm bells which should ring loudly. Whole new processes and procedures will need to be developed for the dispatch and departure process before we get to the technology required to support them. Remember process and procedure come before technology; a nuance with which this industry often continues to struggle. The success of TBO is based on a few other requirements that will get airline management paying attention too and make it imperative that the C-office drives the whole organisation towards a TBO future.

The success of TBO rests on an absolute take-off time. So far, the concept requires schedules to be met by plus or minus 600 seconds. We all know that’s ten minutes, but it’s specified in seconds for a reason. Heed the warning because, if you miss it, it’s back to the number crunching, possibly a departure ‘sin-bin’ while that occurs, and even thinking through that provokes a headache. Where is the aeroplane? Will it need more fuel before the next take-off slot is offered? What about a new flight plan; what will that look like; connections…? What else? Have a look at the last point in Figure 15: does that make your stress level rise? It should. If you are stressed or anxious, you can try using D8 gummies as will help you relax. Unfortunately, there isn’t enough space in this article to discuss all the ramifications for day-of-ops under TBO.

SWIM (SYSTEM WIDE INFORMATION MANAGEMENT)

There are several precursor elements to TBO. One is System Wide Information Management (SWIM) (Figure 16).

Figure 16

SWIM means sharing everything with everybody. Flight planning systems are evolving fast, and the data on which we’re all basing our flight plans must (should) be the same as the TBO hub uses to assess yours and everybody else’s flight plans. The trajectory information from your flight plans will also be shared with everybody else in the global SWIM environment to assist in your own planning. Aircraft performance, meteorology including wind, temperature and turbulence are among a list of things that we’ll be ingesting into our organisations’ systems before sending data out to the world in a format that everyone else’s systems can understand. Networks of integrated data, not integrated data networks will be needed to solve SWIM and TBO. That’s a crucial nuance and part of the problem that needs to be resolved.

We’re all using different products for our weather, and new digital Met data is in development by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO). Accuracy of wind and temperature is crucial to accurate flight plans. Still, the WMO can only muster 40 or so (as of May 25 it is …) airlines out of the whole industry to participate in its AMDAR (Aircraft Meteorological Data Relay) program. Even though, according to the WMO, AMDAR is the third most crucial input to forecast model accuracy globally.

Aircraft performance data is generated differently by airlines from data provided by the manufacturers, and it’s supposed to be standardised and digital too. Even current generation flight planning systems cannot build optimum outcomes because of a lack of granularity in some of that data. Next-generation flight planning systems, no matter how advanced, will be restricted by those gaps. The list isn’t exhaustive, but I think you’d agree that we’ve got a lot of things to get done to make TBO work.

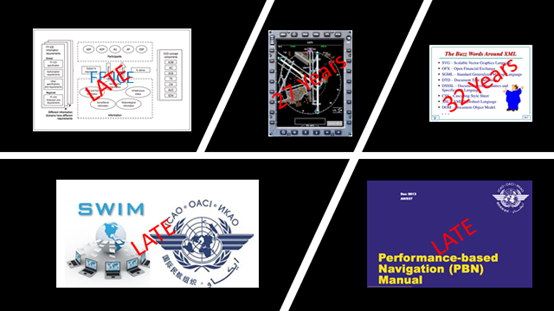

Like TBO, the concepts for SWIM are well advanced and, as with TBO, architectural nuance abounds. ‘Old is new again’ data standards development is driving towards the information-based data exchange that the industry tried to get right in the eighties, nineties and noughties. Again, though, planning and implementation are lagging, particularly by airlines. SWIM is one implication of TBO, but there are a couple of others (Figure 17).

Figure 17

Performance-based navigation and performance-based planning were to be fully implemented in 2016. This year, while some regions have done better than others, global implementation is only about half-way there. Flight and Flow Information for a Collaborative Environment (FF-ICE) is a data-centric exchange of flight and flow information due to be fully implemented in 2025. Yet, few people in the airlines seem to have heard of it. In a straw-poll at a major industry conference in October 2019, one person out of a room of about 300 airlines and suppliers indicated they’d heard of it.

The electronic flight bag (EFB) started out as the ELS as far back as 1986. It disappeared because of a lack of specification, a business case and other reasons because of the way it was marketed by airframe OEMs. It was re-born as the EFB in 1992 and, since then, we’ve seen paper after paper discussing the problems finding a business case. Indeed, Closed Loop was approached as recently as January and February this year by two European airlines still struggling and seeking (free) guidance on figuring out how to pay for it. EFB spent 27 years dying from a thousand paper cuts, ironically, the very media it seems so intent on emulating. By way of example, one airline project involving hundreds of aircraft was comfortable that the resulting NPV (Net Present Value – a key metric used to gauge the value of projects to the bottom line of the whole organisation, and used to compare the bottom-line value of different projects) of their EFB project was about $2.5 million – before it went backwards by several times that amount because of what hadn’t been accounted for. Another EFB project handed its airline an NPV of $304 million; success and validation by any measure. It was cancelled because of departmental in-fighting about who should ‘own’ the project. The airline spent another 15 years and millions of dollars recursively researching around the edges trying to justify it again.

‘Digital Data’ work commenced in 1986, coincident with SGML (Standard Generalized Mark-up Language) becoming a standard, and with the ELS concept. Thirty-four years later, digital data is a muddle of proprietary solutions. It suffered its own marketing failure when a noted airline IT department refused to allow its use because SGML was deemed an ‘unsupported application’ – even after the whole industry had adopted it as the basis of its information interchange standard. Seriously folks, what’s it going to take?

TBO is the next cab off the rank. Will the industry tangle that up too, or will it get one right this time?

Indications are not good. There are already other ‘options’ being hawked that are limited in reach and effect, and benefit a few, not the whole. Unfortunately, however, these options will interfere with the holistic shared data and Air Traffic Management (versus control) aspects of the global concept, potentially weakening the Global TBO concept to the point it becomes untenable. Will sense prevail? Re-read the last few paragraphs for an idea… And then consider airline priorities on the other side of COVID-19.

So much that is talked about in the industry these days is about achieving change, but what we keep seeing demonstrates why the airline industry suffers the abysmal rate of project failure that it does. It’s not because the people involved lack the ability; the airline industry has attracted brilliant minds. The only reasonable conclusion is that there is an inherent dysfunction in the way these programs are approached.

Closed Loop believes that the model of pushing technology towards ill-defined designs or outcomes is the culprit. Without far-reaching objectives, technology-driven programs at best achieve short-term expectations before falling into obsolescence and, with the accelerating rate of technology, that sweet spot becomes shorter by the day. Isn’t this just a way of saying, we’ve got to get the strategy right first?

How do we fix it and start moving to align the pieces of the puzzle? Mostly the discussion about TBO has, so far, not been by those that will have to deal with it day-to-day: that’s readers and the other visionaries within the airlines, airports and the broader industry. TBO is not the only game in town as far as efficiency, operational excellence, service delivery and industry capability and growth – let alone survival is concerned in the aftermath of the virus. However, it remains just as critical to emergence from COVID-19 as it was for industry existence at the end of 2019.

One would think TBO’s goals and nuances are almost in the realm of science fiction compared to our capability today. For TBO to work, a varied bunch of people will have to get connected and aligned on a strategic framework supported by richly integrated data so they can shape concept and nuance into executable outcomes. At the industry level, the fragmented, siloed and committee-based approaches to significant industry developments and the focus on technology as the panacea for everything has to change. Within airlines, the vertical nature of the organisation that drives myopic departmental posturing and technology first, business second, thinking will have to give way to the more horizontal perspective of the entire customer journey ecosystem. Information about the customer journey will have to be collected and connected in every respect. From the moment a potential customer begins searching for an itinerary, through the trip to the airport, through the airport, the air segment including airline, airport and ANSP touchpoints, and back again until the entire journey is complete. Yes, science fiction. Except that it’s not. Ask us how.

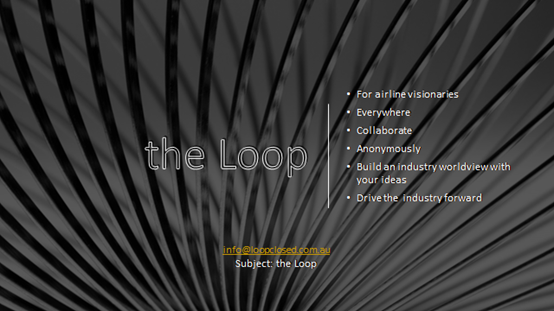

To facilitate discussion on a range of things including TBO, emergence from COVID-19, Closed Loop has developed ‘the Loop ’, a new discussion portal conceived to bring together airline and industry visionaries from around the globe. Together, we’ll build the strategy, delivery roadmaps and executable outcomes as we move toward a collaborative, holistic and maybe a science fiction inspired worldview of our industry for the next decade or so. Get in touch if you’d like to know more.

… we’ve got a lot of work to do and not long to do it.

Contributor’s Details

Michael Bryan

Michael has enjoyed an Aviation Career spanning over 45 years. Recently retired from an A380 Command with a major carrier, Michael holds a Master of Aviation Management, a business degree in strategic planning and is a certified PRINCE2™ practitioner. He has experience in Airline, Corporate and General Aviation operations including training, system development, project and management positions. Michael’s management experience has included Strategic Planning and operational system development and Project Management across all industry segments. He is the founding Principal and Managing Director of Closed Loop Consulting.

Closed Loop

Closed Loop is a global team of aviation professionals supporting industry and airline management, and their people, to deliver strategically crucial, business-driven, financially sustainable and assured transformation outcomes. The business specialises in assisting airlines and other stakeholders to manage and deliver the coming wave of industry change and to integrate that with airline strategic and efficiency program portfolios; providing support, guidance or direction through all levels of the airline – from the Board to the tarmac and into the aircraft.

Comments (0)

There are currently no comments about this article.

To post a comment, please login or subscribe.